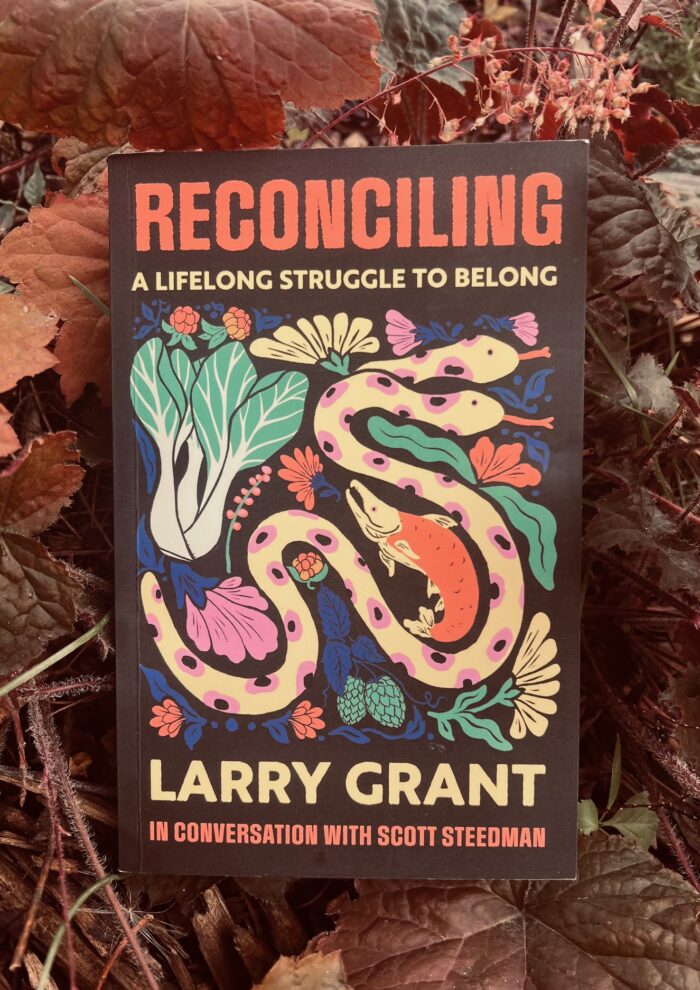

Book Review: Reconciling by Larry Grant and Scott Steedman

I’m writing this review on September 30, Truth and Reconciliation Day here in Canada, a date that recognizes the harms that have been enacted against Indigenous people, and our need to move forward together as a country from this. I’m lucky enough to have the day off work as well, so I’m taking advantage of my quiet(ish) day to review the last book of my month of Indigenous reading, which is Reconciling by Larry Grant in conversation with Scott Steedman. Written as a long meandering story of Grant’s life as told to his friend Scott it reads more like a memoir, and because Grant is given the space and time to revisit his entire 89 years, the wisdom passed on is considerable.

Book Summary

Larry Grant was born in a farmer’s field outside of Vancouver to an Indigenous mother, and a Chinese father. When the local Indian agent discovered that Larry’s mother was married to a non-Indigenous man, she lost her Indigenous status, and Larry and his two brothers were forced off the reserve. They spent their childhood years living in the growing Chinatown of Vancouver which still stands today, but gentrified since then. Even though they weren’t considered Indigenous in the eyes of the law at that time, he still recalls spending much time with family and friends on the Musqueam First Nation, learning his people’s traditional ways of fishing, while also enjoying the vegetables grown in nearby fields by his father and other Chinese immigrants. Although denied his Indigenous heritage as a child, this also protected him from attending the local residential school, which we know was an abusive system where many children died of neglect, disease, and starvation. With an incredible talent for mechanical work, Grant spent most of his working years on the Vancouver docks. He retired, but found a new calling as a teacher, now serving as the Elder-in-Residence at the Justice House of BC and the University of British Columbia’s First Nations House of Learning, helping youths learn to speak Musqueam, as very few living people speak it anymore. There’s a small section of black and white photographs from his life included in the book as well, some photos dating back as early as the 1920s and 1930s.

My Thoughts

Grant’s experience in many ways, was a lucky one. The fact that he was spared the trauma of residential school is no doubt a major reason why he continues to live such a healthy, happy life at his age. His life was by no means easy, but he relates these challenges to Steedman and the reader with a matter-of-factness that suggests his understanding that it could have been much worse, and was, for many of his peers who attended the residential school. Still, he is not accepting of the continuing unfairness that plagued his reserve for most of his life, which pushes him to demonstrate and protest regularly, but also drives him to continue working with youths to preserve the Musquem language, even though he isn’t fluent in it either (no one really is anymore). The slivers of humour and ‘get on with it’ attitude of Larry’s stories are what make this book such a pleasure to read – although the topics are of a serious nature, he’s ultimately just telling the story of his life; the good and the bad. His contentment with his own life is contagious, but he still manages to send the message that we must do more for future generations, that’s our duty as humans first and foremost.

One of my favourite parts of Grant’s book is the chapter in which he visits his Father’s rural village in China with his siblings. They are all elderly at this point, but they had never travelled to see where there father grew up, so together they decided to make the trip, and were surprised to see how modern it was. Their Dad’s childhood was never spoken about, and he moved to Canada when he was a very young man to build a new life, so this place was largely unknown to them. A documentary titled “All Our Father’s Relations” was created about their story, which Canadians can watch for free on the CBC (although not sure about my international readers!).

Grant explains his ‘why’ when telling his story, in the same matter of fact and clear-eyed reasoning the book is written in:

“Larry is writing this book in the hope that all our families and communities come to understand the hardships that many Canadians, especially Indigenous people, still live with today. ‘Hopefully it will get into the school system, so children that have been indoctrinated into white society privilege get to hear about their school mates of colour,’ he says. ‘Children of colour experience racism from birth, so non-people of colour should be able to accept and read about it. Children are very good at understanding fairness and equality'”(p. 83 of Reconciling by Larry Grant and Scott Steedman).

I felt it important to include the quote above because it’s a succinct reason for embarking on this project, but the rest of his story does not read like this – Grant does not shame the reader, or force any opinions on us. Instead, this story is simply his, and he hopes that it will open people’s minds to the told ( or still untold) struggles of those around us.

What an interesting heritage! I’ve enjoyed your reviews of your indigenous reading – they always make me feel I understand a bit more about the past and also about how things are hopefully getting a little better.

Thanks FF! I would say things are definitely getting better, at least here in Canada :)

What an interesting story. I commonly hear the story about indigenous people marrying a white person who lives just off the reservation, but I do know that the word biracial doesn’t mean that someone is white and something else. To my shame, I used to think that’s what it meant until somebody pointed out otherwise somewhere on the internet. I felt stupid for my limited view. It’s also interesting that this memoir came full circle with the children going to find their dad’s village in China. I appreciate that the author gives attention to both of his cultures, demonstrating how they’re equally valued and important.

It is a unique story to be sure, which is why I hope more people read it. Plus, it’s a surprisingly easy read!

Sounds great! I’m glad this book exists!

right? It’s so heartening haha

I’ll be looking for this one! I particularly like reading memoirs from the Vancouver area, particularly ones that offer a different perspective than the European settler history.

This one is definitely rooted in its place, I think you’ll enjoy it. With even the short time I’ve spent out there, it felt like it brought me right back :)