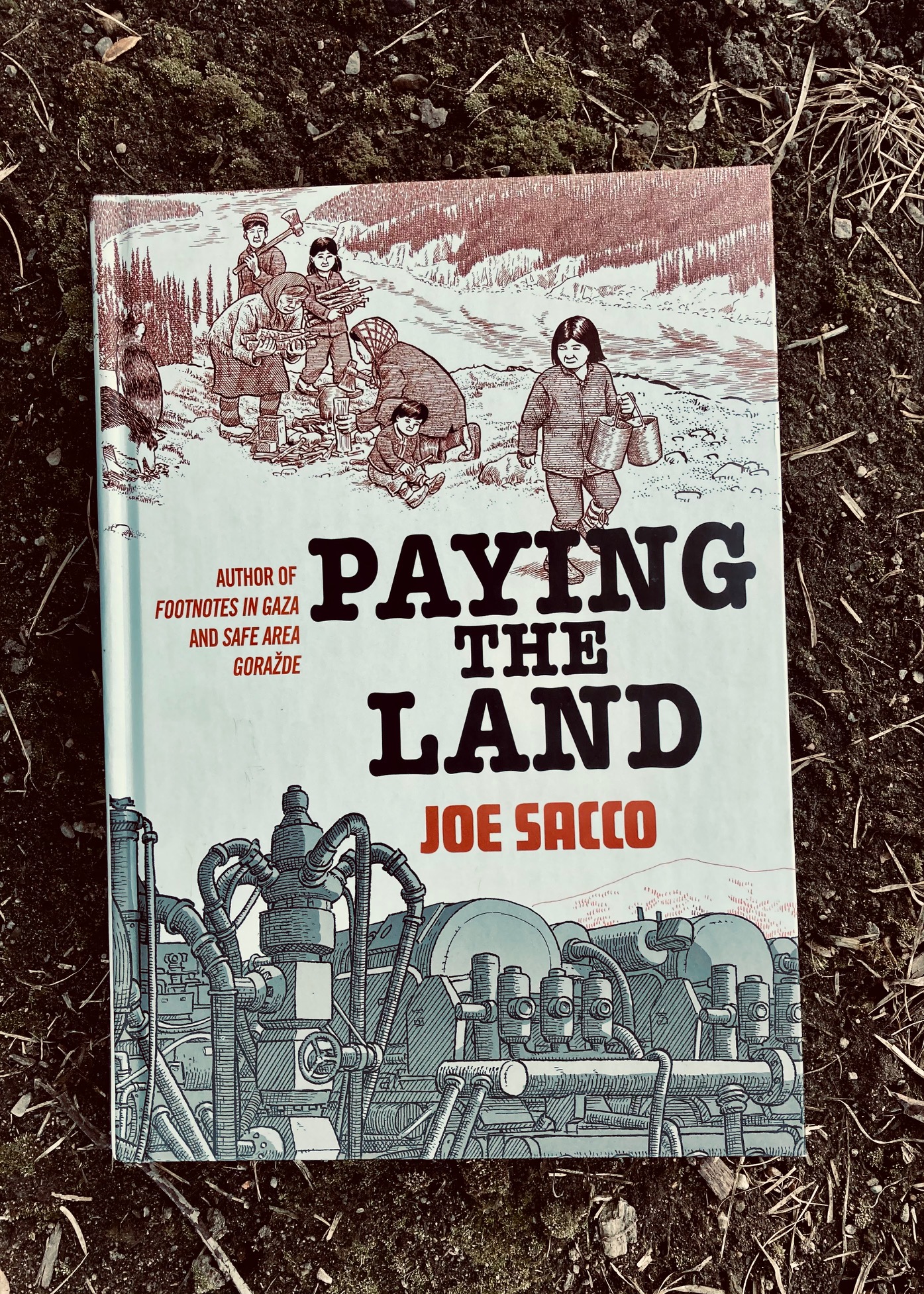

Book Review: Paying the Land by Joe Sacco

It’s important that as you read my review, you understand that this is my first Joe Sacco book. Of course I’ve heard of him, but Paying the Land is the first book of his that has really appealed to me, maybe because it’s rooted in Canada and deals with Indigenous issues which I am fascinated by? Anyway, I’m so glad I read it, it opened my eyes to something I don’t think many people (even Canadians) are aware of, and that’s the conflicting opinions of our Indigenous neighbors to the north. So often we think of, and refer to them as one, but an American journalist has so clearly demonstrated why that is not only unfair, but harmful in the way we speak of, legislate, and interact with First Nations of Canada. Now I want him to write about the American Indigenous Peoples, because I want so badly to learn more about their history as well.

Book Summary

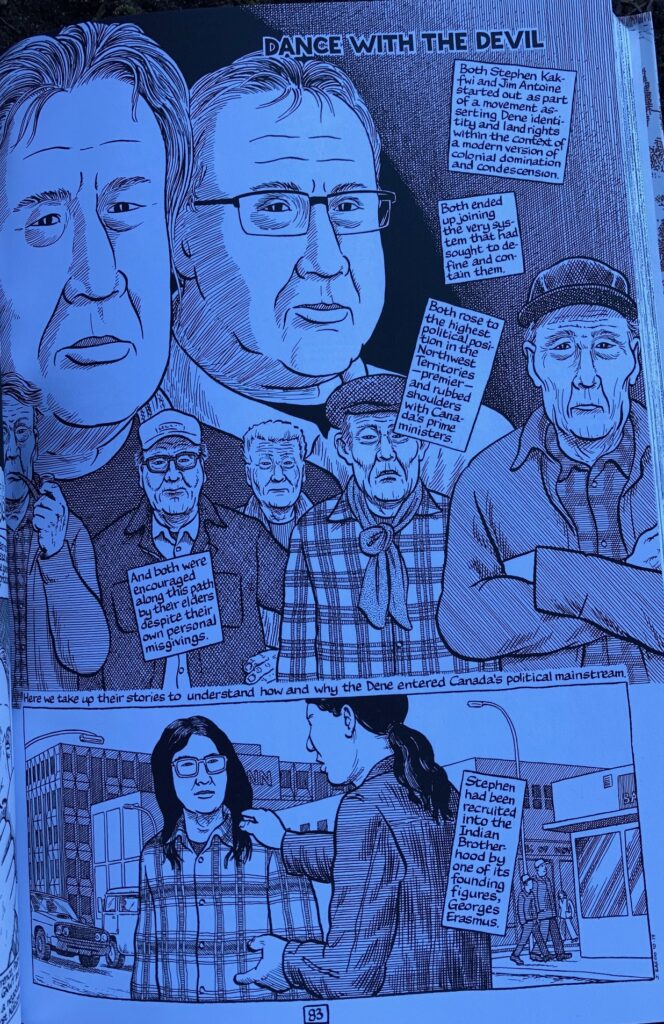

Sacco took a trip to the Northwest Territories of Canada, and this work of non-fiction is essentially a graphic memoir of that experience. He also writes about the original way of life for many Indigenous peoples, which he connects to their present-day life and how resource extraction has altered it. There is a significant portion of the book dedicated to explaining the horrific experiences of residential schools, of which Sacco gathered first-hand testimony of. It is Canada’s dirty not-so-secret anymore, and even though I thought I had heard the worst of it, this book touches upon even more disturbing details Sacco’s interviews uncover. Residential schools all weave into the overall understanding of our northern communities and the challenges they face. Surprisingly, another topic dealt with in great detail is the land agreements and political maneuvers that happened over the years as the Canadian government became more and more interested in mining that land for it’s natural riches. There are many different leadership figures in the northern First Nations introduced in this book which made it difficult to follow along at times, but Sacco excels at demonstrating the variety of strategies, opinions and viewpoints within the indigenous populations that can be found in this area of Canada.

My Thoughts

It seems odd that such a perceptive, empathetic, and informative book about Canada’s northern Indigenous communities has come from the pen of an American journalist, but here we are! So many stories about the Indigenous experience have a motive, and although I don’t think that’s a bad thing, it’s a vastly different experience reading a book by a journalist who is just clearly fascinated by this complicated landscape and the people on it. Although it seems almost impossible, Sacco stays as apolitical as possible, giving every side a fair chance to state their opinion and why they feel that way. The illustrations themselves do most of the persuading, the terrified looks of children under residential school care are striking, and those sections in the books are particularly haunting. Still, they are incredibly important in offering context of how this system (regrettably) shaped Canada’s Indigenous population, as well as explaining the affects of intergenerational trauma.

The majority of the book is incredibly serious, but there are small glimmers of humour when Sacco pokes fun at his lack of outdoor experience. Life in the north is not easy for anyone, and he’s lucky to have a guide (Shauna) who is adept at learning new skills on a snowmobile, but his incredulity at how remote some of these communities are is something most people can relate to. I may be Canadian, but I’ve never been that far north before, so in some ways this book read a bit like a travel memoir.

The Indigenous reverence for the land and the importance of its protection is something that all of Sacco’s interviewees agree on, but their opinions on how the land should be used is what varies. The depressing cycle of alcohol abuse, welfare, dying economies and a lack of jobs is a war fought by many communities, yet it is more prevalent up north because of the residential school system, a boom/bust economy based on resources alone, and the general remoteness of the villages. I appreciated the fact that Sacco sought out younger indigenous leaders who want to remain where they grew up, with a connection to their elders and their land, but are also forward-thinking enough to realize that something needs to change in order for them and their families to have a prosperous life. Their optimism and fierce loyalty is a bright ray of hope in the book, and one that I was excited to read about. Once again, this is yet another book about Indigenous populations that every Canadian should be reading. I know I say that a lot, but I really do feel like reading and educating ourselves about the various challenges, struggles and triumphs they face will help us on our road to recovery, or at the very least, reduce the rampant racism indigenous people face here, and elsewhere around the world. The fact that this book has beautiful illustrations to accompany this education is a welcome bonus.

This one’s on my TBR! And I know what you’re saying about the idea of it being strange that an American journalist is covering this topic, but I think it seems strange because of the way that Canada continues to stress its ownership of and control over these communities and people rather than recognizing them to be independent and sovereign nations in their own rights.

We’re immersed in this idea from an early age…you even have the possessive form there, but I’m sure you don’t intend to say that these communities are Canada’s people. These habits and ways of speaking and thinking are not necessarily easy to spot, so I don’t mean to be critical in pointing it out, rather to remark on how deeply ingrained these ideas are in Canadian culture. If we were to think of these communities as independent, I don’t think we’d have the same kind of expectations about which country’s journalists (now I have to doublethink that possessive!) would be more/less likely to want to explore and study them?

I totally get what you are saying! I try to avoid calling them ‘our first nations’, b/c I know using the possessive is doing them a disservice. But I do need to look closely at the other terms I’m using b/c I know I haven’t eradicated it from my vocabulary. It would be interesting to read about the various Indigenous perspectives on whether they consider themselves Canadian. As in, I’m assuming most consider themselves Indigenous first, but where does Canada lie on that spectrum for them?