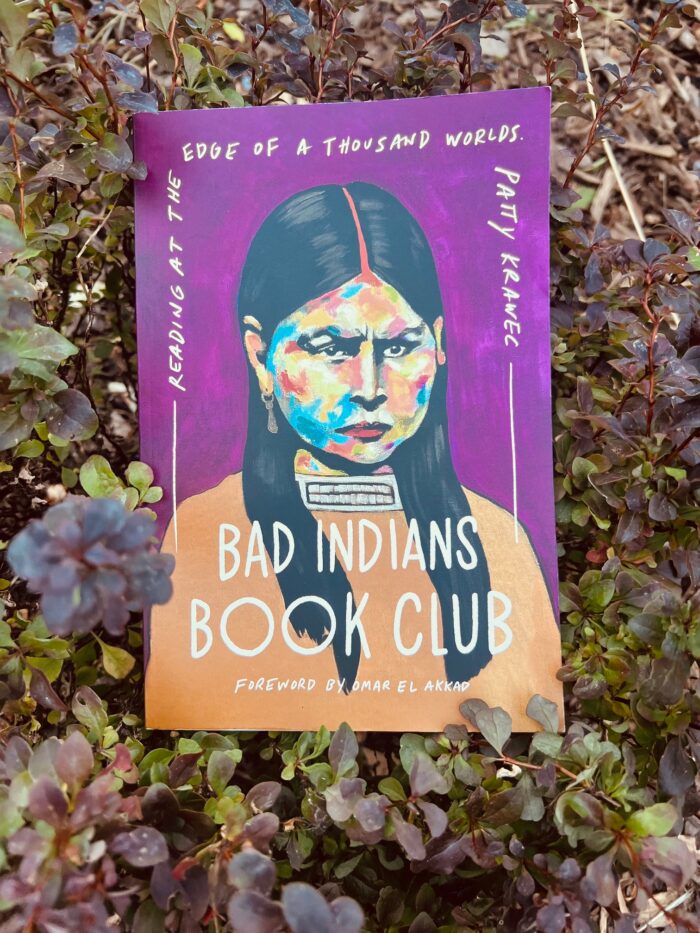

Book Review: Bad Indians Book Club by Patty Krawec

I’ve mentioned before how much I enjoy books about books, so when Bad Indians Book Club , Reading at the Edge of a Thousand Worlds by Patty Krawec came across my doorstep, I jumped at the chance to read it. This is a work of challenging non-fiction as it comes across more as an academic text than a book club advice manual or reading guide, but I’m always looking to stretch my reading skills so I’m glad I gave it a chance. For those who actively seek out writing from marginalized folks this will be a particularly fascinating book, as it blends opinions and quotes from not only Indigenous peoples, but many of those whose culture or race has ever been under attack. Black and Jewish writers play a predominant role in those who are referenced, so Krawec widens her scope in a way that forces readers to consider the harmful effects that colonialism, racism, and xenophobia have had, and the way writing can become resistance against these forces.

Book Summary

Split into nine sections, Krawec follows a year of reading about “Bad Indians”, i.e. those who will not conform to the stereotypes that colonialism has thrust upon them. Krawec also taught classes on these themes as well as recorded podcasts on them, so at the back of the book is a long list of additional resources one can further explore, in addition to the numerous footnotes. The eight writing themes are: Clearing Space for Story, Science and Nature Writing, History, Stories about Refusing Patriarchy, Memoir, Fiction, Horror, and Speculative Fiction. The ninth section is a work of fiction by Krawec that breaks up the literary analysis; it’s a story that takes place over hundreds of years, following a female character named Kwe who shifts from a human to a deer shape, as she witnesses the transition of the Americas from pre-colonial time, to the present day.

My Thoughts

Krawec introduces herself as a Bad Indian at the beginning of the book, which by her definition, “are experts at refusal and creating hostile spaces, and we tell our own stories, even when they aren’t pretty.” (p. 21, Bad Indians Book Club by Patty Krawec). Omar El Akkad echoes these sentiments in his foreword when he refers to the “Grateful Immigrant” and the “Untroublesome Minority”. I found these phrases particularly striking, because I think this is the root of so much racism – if you weren’t born here, shouldn’t you be grateful you were allowed in at all? But how do we square that with our expectations of Indigenous folk, who are truly native to this land, then got pushed into reserves across North America – why do we still expect them to be grateful? Because they are now the minorities?

Canadian readers will appreciate the references to numerous Canadian authors that they may already be familiar with. I personally found I could understand Krawec’s arguments quicker when I was familiar with the books she was using as an example. Her analyses of genre fiction written by Indigenous people were most fascinating to me, including the following quote from a character in a work of speculative fiction by bestselling Canadian writer Waubgeshig Rice:

“Aileen, one of the elders in Moon of the Crusted Snow, tells Evan, the protagonist, that we don’t have a word for apocalypse-and that the world isn’t ending anyway. The world actually ended for us a long time ago, she says, when the settlers arrived. We’ve been adapting and surviving ever since” (p.199 of Bad Indians Book Club).

Akkad’s foreword introduces his relationship with the author this way; she sent him a message after the release of his famous book American War which I review here, basically asking where the Native population was in his breakout book – they were never mentioned, and she felt this was an obvious gap. He graciously admitted that she was right, which began a relationship between the two writers, even prompting Akkad to include a reference to Indigenous populations in a future novel of his. And this is what much of this book truly is – a dialogue. The ideas don’t feel fully formed, similar to a discussion during a book club. Instead Krawec cites other authors and their work to expand our thinking of Indigenous writing and how it’s reflective of the experiences of Indigenous people. Often Indigenous writing has been forced to defend itself or educate settlers, but as it gains in popularity, it has flourished in other ways, now becoming a pushback against the corners they have been relegated to. The expansion of Indigenous and marginalized writing and publishing allows us to see different facets of the Indigenous or marginalized experience that have previously been hidden, or in many cases, punished.

All in all there were many moments of reading this book where I felt a bit lost as some of Krawec’s ideas were hard for me to truly grasp, but there were many more ‘aha’ moments too. For those who want to explore more writing by Indigenous folks, I recommend dedicating some time to this book as well as taking a few examples from the extensive bibliography. It’s a challenging read, but worth the effort.

Given the tone of Becoming Kin, I’m not surprised this takes a bit of work, but it sounds like you found it rewarding enough to persevere. I love the idea of simply introducing ideas and then allowing conversations to unfold, it sows the seeds for growth all the way ’round. (I’m on the hold list at the library…I hope it arrives before the snow does!)

Yah, I liked how open-ended she left it. It felt almost like a book club discussion in a way..