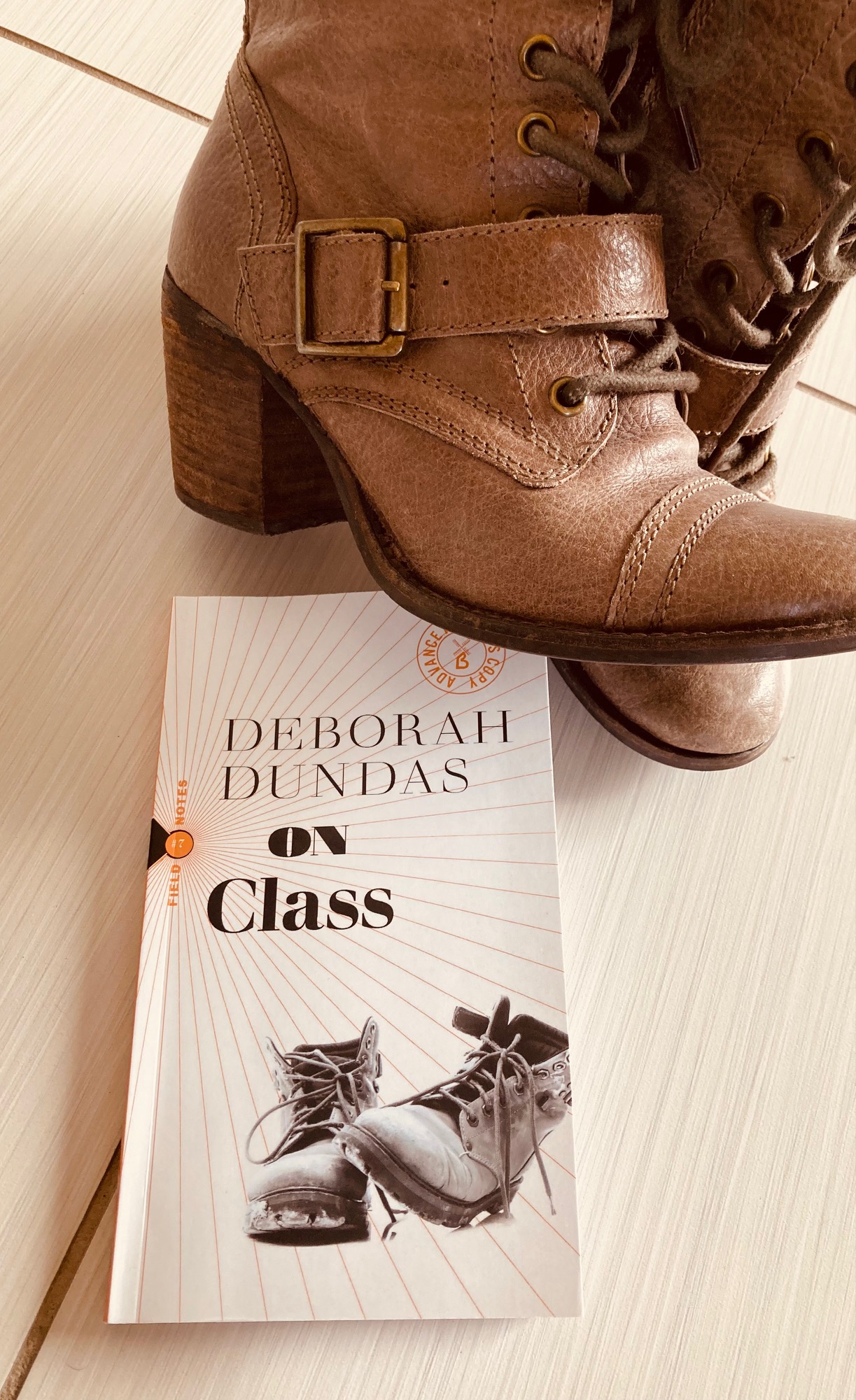

Book Review: On Class by Deborah Dundas

If you’ve ever wished yourself out of a conversation at a social event, try bringing up the colorful subject of personal wealth – and watch people disperse immediately! On Class by Deborah Dundas is the seventh in the Biblioasis Field Notes series. In this short, pamphlet-like book, Dundas explores the complicated world of class; the lower, middle, and upper classes, how we define each, and society’s myths and mistreatments of those who live in poverty. In only 135 pages, Dundas lays out worthwhile and thought-provoking points on a topic so very rarely discussed out in the open. Instead of learning about poverty from a politician’s mouth, I invite you to read this extended essay by someone who grew up in poverty instead.

Book Summary

Dundas succinctly divides this admittedly massive topic into 5 digestible sections; privilege and expectations, fitting in, voice, community, and beyond the hero narrative. The ‘expectations’ section offers an interesting perspective; how does one’s parental class and expectations affect your mobility upwards or downwards? ‘Fitting in’ is all about the shame of being perceived as lower class. Those who are lifting themselves out of poverty have different expectations of themselves and likely lack confidence as they try to remain upwardly mobile. The ‘voice’ and ‘community’ sections touch upon who we speak to, and who we consider when looking to give poverty a voice, and why those who have come from poverty often don’t feel comfortable talking about their past. The ‘hero narrative’ speaks to our society’s habit of looking to those who worked their way out of the lower class, and holding them up as a standard. If we continue to believe hard work alone will eliminate poverty, then we can absolve ourselves of the guilt that comes with the increasing wealth gap. The conclusion of the book is a story of Dundas closing down her mother’s apartment after her death. Her mother was a woman who lived on very low income so there isn’t much to do, but it’s a sad reminder of how tenants of low income housing are treated by their landlords, a popular topic right now as inflation continues to squeeze renters even further.

My Thoughts

Despite its very short page count, there’s much to be discussed and pondered in this book. I don’t typically enjoy philosophical texts, but the philosophy behind class and our society’s conflicting viewpoints of it is one that I find endlessly interesting. Admittedly, the fact that I can even find a topic like this interesting points to my own privilege – I’m not poor, and I’ve never been poor, so it’s not a source of shame or discomfort for me. But as a fundraiser for a social services program, I often find myself straddling two opposing worlds; those of the wealthy I am speaking to, and those who I am raising money on behalf of. Ultimately I need our prospective donors to understand why we help those we do, and why helping them is a worthwhile use of their money. But I’m often speaking to people who have worked really hard too, and they often subscribe to the “bootstrapping” idea that as long as you work hard, you will succeed:

“These stories serve to reinforce the myth that our forebears came here and carved out a life for themselves: but most were subsidized by government to settle here, often by being given land stolen from Indigenous people. Did they work hard, our forebears? Undoubtedly-but they didn’t do it entirely on their own. Hard work isn’t erased by support; the two aren’t mutually exclusive.”

-p.120 of On Class by Deborah Dundas, ARC edition

Lots of people with privilege also work hard, which is a nuance that often gets skipped over – people who are identified as having privilege have a tendency to get defensive about this because they feel like it erases all they’ve accomplished, which it doesn’t. Acknowledging privilege simply allows space and consideration for those who haven’t had similar success, and an invitation to empathize with those who have had different life experiences or navigated difference circumstances.

One may ask why she of all people has chosen to talk about the concept of class. Dundas’s ‘day’ job’ is the book review editor for the Toronto Star, one of the few major newspapers left in Canada, so she herself is seen as having an enormous amount of privilege – she is one of the few gatekeepers left controlling access to print books coverage, a valuable commodity these days. But as Dundas explains in the introduction she grew up in poverty herself, and it still influences her today, even though she is now firmly ensconced in the middle class. To offer a balanced argument, she includes interviews of people in each section, from all classes. Even professors and academics who specialize in class difference and its affect on society and the economy are cited. Never once did I feel as though the text was preachy, or moralizing. It simply shines a light on a topic often avoided, and I’m hopeful this book will get more people talking.

This is such a great series; some of them I’ve read from the library but I think they’re the kind of books one could reread occasionally (in part, at least) if one owned them all. Such complex ideas but clearly expressed…and so relevant!

I haven’t read many, but this one was so awesome. Glad to see you back on here Marcie :)

Sounds interesting and also as if class is treated rather differently in Canada to here. Here, people tend to be proudly working class and even if they’ve moved into the middle or professional class, they tend to boast about their working class roots. Reverse snobbery!

I feel like I need to read this book. In the past year I’ve been accused of being privileged many times. What people (classmates) are referring to is the way that I have more time to do school work, and I don’t have a job. However, it’s always said in a snide fashion, as if I didn’t work my ass off when I was 18. When I was an undergrad and earned my bachelor’s degree, I worked midnights full time and went to school all day, taking 21 credit hours. However, I can see how not having a lot still affects me, especially with food. I get nervy that there isn’t enough, or I should eat a lot when it’s there because it won’t be there later.

Man that’s annoying your classmates resent you for your extra time. How people choose to spend their time is up to them, like, even if you didn’t work your ass off when you were 18, who cares? Judgey mc Judgersons.

But yes, I think you’d really like this book, I wonder if its available where you are??? I hope it is! I can always mail you a copy if you can’t get it.

Ayyyy, my library has it!

NOICE!