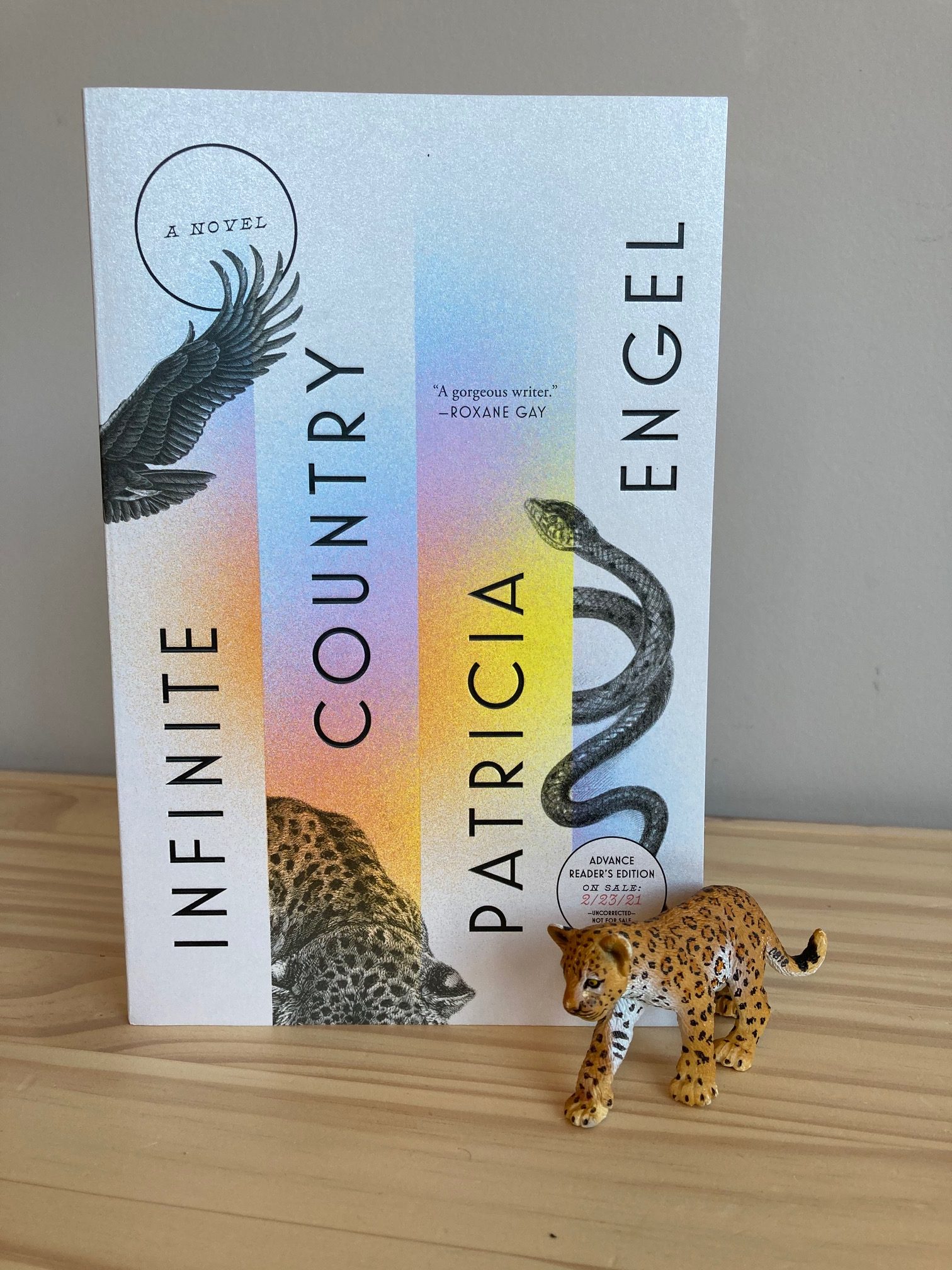

Book Review: Infinite Country by Patricia Engel

It seems strange to admit, but the cover of Infinite Country by Patricia Engel is the first thing that drew me into it, which is rare for me; I’m rarely swayed by the cover of a book, but I loved the metallic rainbow panels in between the detailed pencil sketches. These three animals, the condor, the jaguar, and the serpent all weave their way into this book’s mythical bedrock that cements each character’s connection to the land. How we define ‘our land’ and ‘our home’ is at the heart of this book, and not surprisingly, there are no easy answers.

Plot Summary

Elena and Mauro live in Bogota, and they fall head-over-heels in love, finding refuge in each other’s arms while violence rages around them. They are both quite poor, and finding themselves pregnant and unwed, Mauro vows to make a better life for his family, convincing Elena to take a trip to the U.S. shortly after their daughter Karina is born. They arrive with visitor visas, but decide to stay illegally once they discover how much more money they can make working in America, the opportunities seemingly endless compared to the ever-increasing danger of Columbia. After the birth of their third child Talia, Mauro is caught and deported, and quickly realizing the impossibility of raising a newborn and two other kids as a single working mother, Elena sends Talia back to Columbia to live with Mauro and her mother Perla. This fracturing of the family proves to be too much for Mauro as he falls deeper into alcoholism, wracked with longing and guilt for his wife and other children. While the book begins with Talia’s account of escaping a girls reform school, (which can be a bit disorienting) Infinite Country is more focused on the lives of Elena and Mauro, and the sacrifices they make as parents. Talia’s perspective is that of a new generation who lives with the knowledge that her parents left to make a better life for her, yet she has little to show for their brave actions.

My Thoughts

Some of you may find this shocking, but this book is less than 200 pages long! Yes, an entire family saga told in 191 pages, so don’t tell me that 800 pages books are a necessary evil. Engel has produced a tightly-written narrative with more than enough threads to keep even the most astute reader on their toes. Despite its short length, the plot still feels full, the characters thoughtfully fleshed out, and enough description to conjure a believable setting. Unfortunately the switch between perspectives and time periods muddled my focus, especially when symbolic myths were explained by various characters to further explore the ideas of home, borders, and land ownership. But all these aspects of the story came together to form a lasting and authentic view of the immigrant story that we see so much of in both fiction and non-fiction these days. And why shouldn’t we? Immigrants, refugees, ‘illegals’, they each have a story, and the more we learn about why people leave, how they leave, why they stay or don’t stay, teaches us how to make life better for both ourselves and each other.

One thing I found surprising was Elena’s indifference to, and even resentment of America. I was fascinated by this unique development in what seemed to be developing into a classic immigrant story. It’s Mauro who pushes Elena to leave Colombia and to stay illegally in the U.S. She considers going back once he is deported, but other immigrant women urge her to reconsider, for the sake of her children’s futures. Elena constantly questions everyone’s desire for the ‘American dream’:

“What was it about this country that kept everyone hostage to its fantasy? The previous month, on its own soil, an American man went to his job at a plant and gunned down fourteen coworkers, and last spring alone there were four different school shootings. A nation at war with itself, yet people still spoke of it as some kind of paradise.” (p. 90 of ARC).

Elena is well aware of the violence she left behind in Bogota, yet that’s home to her. In America, she’s treated poorly, but those around her urge her to be thankful she’s still able to live there, even if it’s in hiding. This contradiction is something that Elena struggles with throughout the novel, because being in the U.S. seems wrong to her, but she doesn’t leave for fear of what could happen to her and her children. The only true dream that Elena has is to be together as a family again, whole, and living without fear, yet this seems to be an impossibility, no matter what choice she makes. So many of us in developed nations take this privilege for granted.

The book makes an abrupt shift when we are given a few short chapters written in the other children’s voices, the ones who grew up in America and have never been to Colombia. They are teenagers struggling to fit in at school, facing racial taunts and slurs on a daily basis. Taking advantage of the fact that their mother doesn’t speak English, they translate their teacher’s messages incorrectly to Elena, protecting her from the worst of their situation. The skill necessary to fit all this into such a short book is impressive, and although there are numerous reasons to read it, the taut plotting and narration is one of the most remarkable aspects of Engel’s writing.

I admire succinct stories like this, but I also enjoy a thick family saga: do we have to choose? :)

A few weeks ago, I watched Ai Weiwei’s documentary “Human Flow”–amazing. And I’d’ve taken a second look at this cover too.

We absolutely do not have to choose, i think it’s pretty common to like opposing storytelling styles too :)