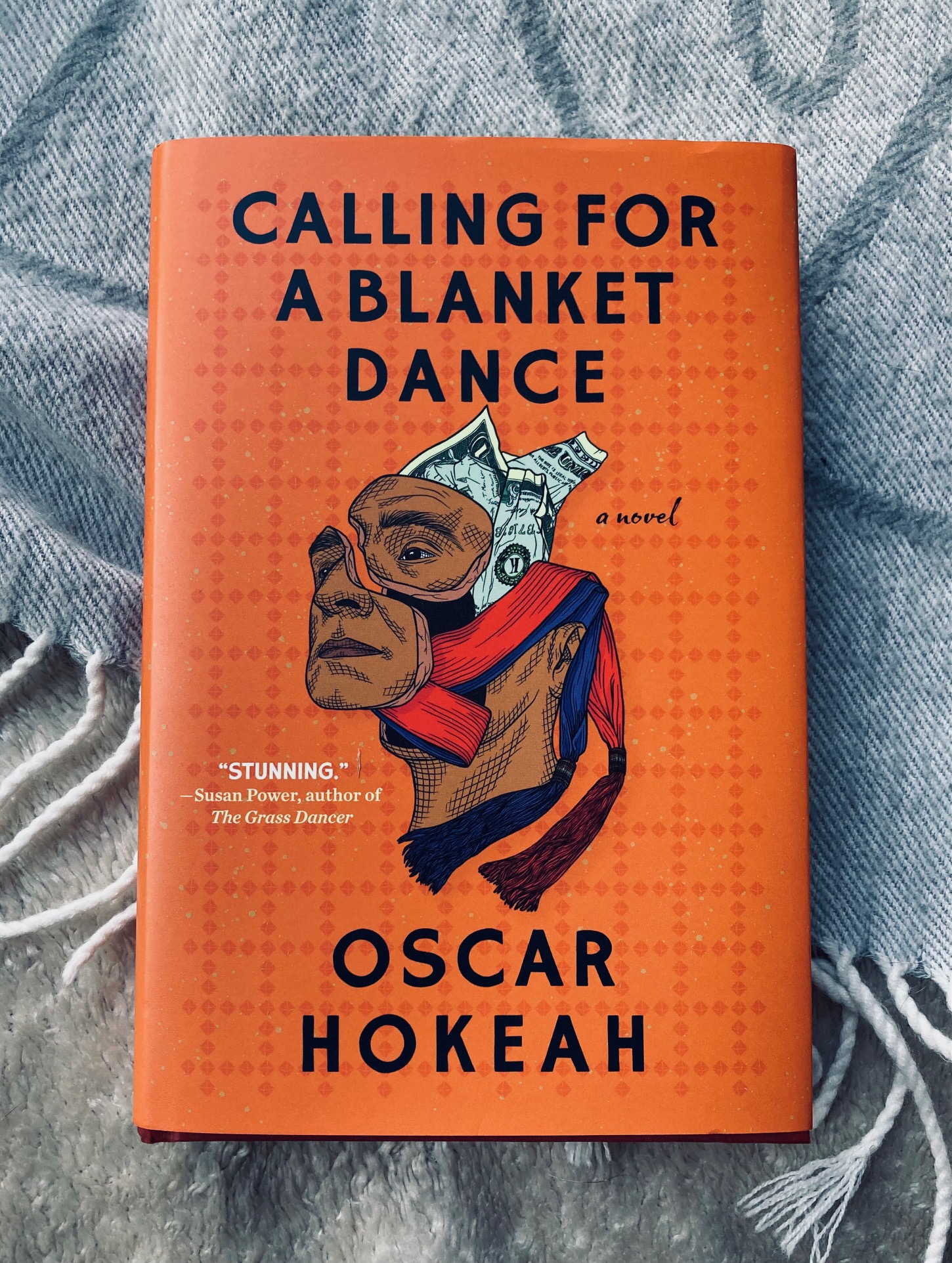

Book Review: Calling for a Blanket Dance by Oscar Hokeah

Here in Canada we are lucky to have a rich publishing landscape of Indigenous voices, and the numbers are only increasing. In fact, many books on the current and previous bestseller lists are Indigenous writers. I don’t see the same representation in American publishing, and I heard the Native American writer Tommy Orange speak when he was here in Calgary, and he echoed the same thoughts – the U.S.A. publishing industry has a long way to go in properly representing this population. With this in mind, I’m always excited to pick up Native American authored books, so I requested Calling For a Blanket Dance by Oscar Hokeah as soon as I saw it in the catalogue. It speaks of trauma and hope, a common theme in many books by Indigenous folks.

Plot Summary

Written in the style of a collection of short stories, each chapter is written from the perspective of one member of the extended Geimausaddle Family, each within a specific year. The stories are spread cross the generations, beginning with the matriarch Lena in 1976, and ending with her grandchild, Ever in 2013. There is (thankfully) a family tree at the beginning of the book, which I referred to often. This family is of mixed heritage; Cherokee, Mexican, and other indigenous tribes that weave in among these as more people are absorbed into this family’s circle. The majority of the stories take place on reserves, while violence, drug abuse, petty crime and poverty are a common thread throughout. Some kids manage to escape these harmful influences, while others fall headfirst into them. The book ends with a blanket dance. For those who don’t know (and I just looked this up myself) a blanket dance is part of a traditional powwow, meant to raise money for those who travelled there; a blanket is spread out, and people are asked to drop cash on the blanket for the recipient. Ever’s story ends with a blanket dance held in support of him and his four kids; he is a single father struggling to make ends meet, and the generosity of his community is a beacon of hope in his complicated and difficult life.

My Thoughts

Most books by Indigenous authors today deal in some way or another with trauma. This is an un-escapable fact, and I think it’s unfair of us white people (settlers) to expect otherwise seeing how fresh many of these racist laws governing them were. It isn’t until very recently that Native and Indigenous rights have come to the forefront of society’s conscience, and we still have a long way to go. These unfair and destructive policies are reflected in the pain this book’s characters are working through. And like many small towns in America, meth is a problem in this book too, destroying the lives and livelihoods of people of all ages. Despite this sadness, I love and continue to search out books about these populations because even though they depict a horror I can really only imagine, the beauty that is also depicted resonates with all kinds of readers. In this book, hope is found in the overlooked places; the exhausted mother who reads to her kids through her falling eyelids, the adoption of a foster child with violent tendencies, the supportive sister-in-law who does late-night pick ups after work. Kind and loving deeds counteract the harmful situations and destructive actions, even if they are harder to find.

Hokeah’s writing also acts as a balm against these painful circumstances, which help balance out the harrowing scenes depicted in this book. His description of a man struggling with alcoholism is as poignant as the repurposing of salt shakers as an act of defiance:

“A full whiskey bottle was as light as air. Real easy to lift to my lips. An empty? It weighed like a mountain…”

-Calling for a Blanket Dance, p. 33

“…the U.S. government didn’t allow us to practice our culture. The only thing we had were government rations called commodities, and in those commodities were tin salt and pepper shakers. Most looked at them and saw salt and pepper shakers, but we looked at them through Kiowa eyes and we saw gourd dance rattles…When Kiowas danced with rattles made from tin salt and pepper shakers, it was a proud act of resistance.”

-Calling for a Blanket Dance, p. 61

The above quotes were both taken from the same chapter and the same man. Many characters (especially the men) embodied both pain and hope. Women seem to take the brunt of abuse and neglect in this book, left to pick up the pieces and take care of the kids the men abandon, while the male characters are described in often contradictory terms. Ever is an aggressive young man, dangerous even, but he grows to be a stable parent in his own time.

This was a heart-wrenching read that I was simultaneously relieved and disappointed when I came to the end. Witnessing this family’s pain is difficult, but rejoicing in their wins overshadowed the suffering they rose from as well. I highly recommend this book for all those reasons, but especially for my fellow Canadians as we continue on our journey to Truth and Reconciliation.

You’re right about Indigenous representation in Canada vs the US. We’re very fortunate. This sounds very good – I’m adding it to my list.

This is on my list. It sounds amazing. Sometimes I can handle sad books, sometimes I can’t, but I want to give it a try.

There is joy in this book too – you just have to search a little harder for it :)

There is so little representation in the United states, and when I’ve tried to get books that you’ve recommended in the past about indigenous people, I ran into barriers with publication laws, or whatever. One book I ended up getting directly from the publisher through some kind of digital workaround the publication laws. I really like the quotes that you shared in this book, and I’m keen to read it, but we’ll see if I can get my hands on it.

Hopefully this one should be easier to find!

I found it! My library has it in all formats.

nice!

Okay, I’m about 55% through this book, and while I’m interested, the narrator choices are bizarre. Each chapter is a different person, right? So, why choose the grandmother to narrate a story about her daughter and infant grandson, when the grandmother wasn’t even there? She’s tangentially related to the story because her daughter asks her for money to help out, but it’s just weird that she’s telling us things that happen that she never experienced. I get the each person is basically talking about Ever, but I wonder what led the author to choose this style of narration.

Hmm maybe I’m not remembering it correctly, but isn’t every chapter written in the first person perspective?

Yes, it’s all in first person by different people. However each person is telling a story about the main character, Ever. So, for instance, the story in which ever is an infant in his dad gets beaten up in Mexico? That story is told by Turtle’s mom. That’s the bizarre thing to me. Why not have the story told by Turtle or Eduardo?

Oh yes, now I remember. That first story about him being beaten up. You are right that was an odd choice! I was thinking of the later stories…

In some interviews, Oscar Hokeah said each chapter is kinda like that person’s idea of “the important event in Ever’s life that explains who he is”. So, for example, to Lena the defining event of Ever’s life is that one horrifying border crossing when he was a baby. He said that in a blanket dance, individuals come and dance alongside the person asking for help as they throw down on the blanket whatever they can contribute to help out. And these stories were the various characters’ ways of coming alongside Ever, telling The Story of Ever (as they know it), and supporting him along the way.