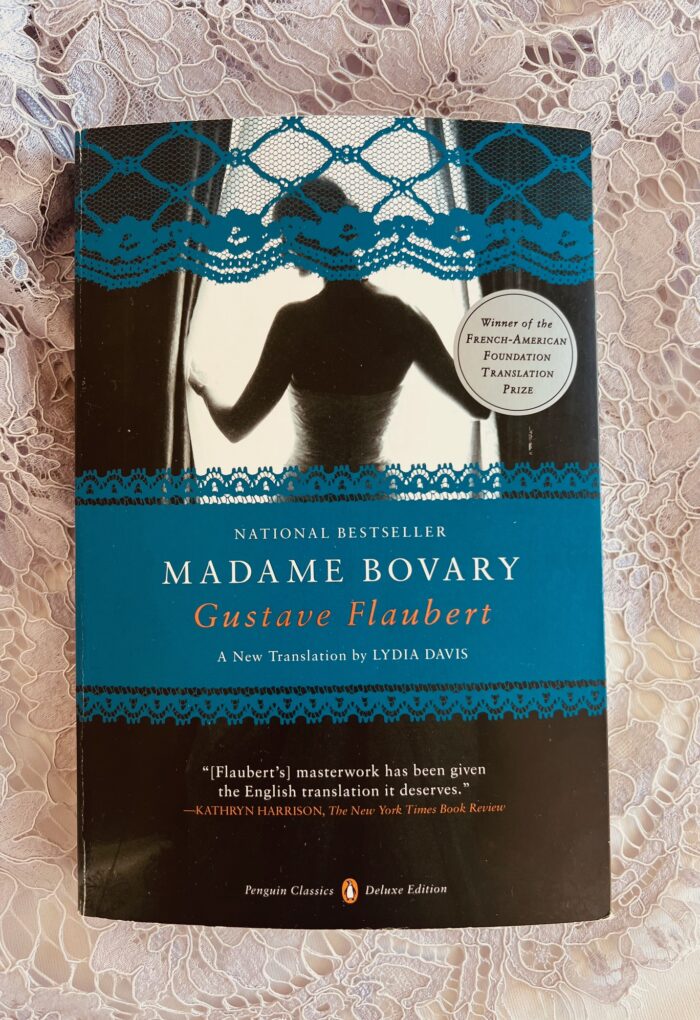

Book Review: Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

I’m typically that book blogger that comments wistfully on other read-along posts, lamenting the fact that I want to participate in all these group book discussions, but stuck with my reviewing schedule that aligns with my radio segments instead. Maybe I was feeling particularly motivated the day I came across FictionFan’s Madame Bovary review-along invitation, but abandoning my previous excuses I purchased my copy of Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert right away, essentially forcing myself to stick with it. And because I really wanted to get the full bookish community experience, I chose the same French to English translation as FF, which is by Lydia Davis. I don’t read classics often, but occasionally I’ll dabble, and although I didn’t fall head over heels with this famous story I’m glad I read it, and I’m looking forward to seeing everyone else’s thoughts on it too.

Plot Summary

First published in 1857, Madame Bovary depicts the life of a lovesick and fanciful young woman named Emma. She marries physician Charles Bovary after the death of his first wife, eager to start a life with a man who appears to be steadfast, trustworthy, and most importantly, head over heels in love with her. They move to the countryside so Charles can grow his medical practice, but she quickly finds herself bored and restless with her new life. They have a daughter, Berthe, but this doesn’t seem to fill the hole inside Emma’s heart. Instead, she embarks on a series of affairs, becoming more desperate and lovesick with each rendezvous. If this wasn’t bad enough she spends what little money they have on purchasing herself luxuries they can’t afford, more as a distraction than anything. Despite her suspicious behaviour and manipulative actions, Charles remains utterly infatuated with his wife, content with his family and happy to continue working as much as he can to fulfill her increasingly bizarre requests. To avoid spoilers I won’t say anymore, but beware of the introductions to classics such as these, as many will have spoilers as part of the literary analysis. This particular translation does include spoilers in the introduction too, but it helpfully warns readers of this first so I knew to leave it to the end. I do recommend reading the introduction at some point though, it includes fascinating information about the author and the history of the Flaubert’s legal troubles.

My Thoughts

When one is used to reading some much modern fiction like I am, I find it takes about 50 pages or so to really adjust to the different style of writing from that time period – and I’m not just talking about older rhetoric or sayings. What struck me about this book was the fact that it moved so slowly and deliberately through the plot, building into a subtle unease that the reader is expecting, but discomforting nonetheless. There are lots of ornate descriptions of course, but this is largely because it’s such an interior novel; we spend the majority of the time in Emma’s head. The scenes that felt the longest to me were the ones that depicted the metaphorical ‘dance’ between Emma and her lovers before their affairs begun, but perhaps this is more of a reflection of the societal expectations of that time -did these hookups simply take longer back then? In our age of instant gratification the amount of pining that Emma does seemed almost unbearable to me, even their act of writing daily letters to one another feels otherworldly, but these slower ways all amount to a story that plods rather than races along.

Although it’s tempting to fall into the trap of discussing how I felt personally about Emma, I don’t think that’s helpful when reviewing a book like this. I’m sure most people would agree she’s foolish and self-centered, but I also wonder if her actions are those of someone who is seriously mentally ill too. She most definitely finds herself in the throes of depression, but she also has a strange and shifting obsession with religion, which mimics episodes of mania. And she can’t be blamed entirely – her first lover is clearly a jerk, and we are subject to his interior thoughts early on so it’s clear he’s not a nice person. Her second lover seems more genuine, but it’s continually her husband Charles that is depicted as the ‘best’ of all these characters, if not a bit clueless. One of the more entertaining characters is the local pharmacist, who says all the wrong things at all the wrong times, but I couldn’t help but enjoy his odd commentary. He also seems to love his wife very much, which works in his favour.

These bits of humour were not always intended, and I think modern audiences will have a laugh out loud moment like I did when I read the following quote. Emma was trying to convince Charles to pay for her piano lessons (a ruse to meet her lover), but he is hesitant because they can’t afford it. The pharmacist observes this conflict, and tries to helpfully intercede:

“‘Besides, keep in mind, my good friend, that by encouraging Madame to take lessons, you’ll save money later on your child’s musical training. My own belief is that mothers ought to teach their children themselves. This is one of Rousseau’s ideas; it’s perhaps a little new, still, but it’ll end by prevailing, I’m sure, like mothers breast-feeding, and vaccination'”

-Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert, p. 94

Although we’re still waiting for vaccinations to prevail, much of what the book depicts is currently being played out in households across this world, in 2025. The only differences is that texting and Tindr are the vehicles of marital affairs, rather than letter-writing and local country balls. In many ways it’s comforting to know that not too much has changed, and when it comes to matters of the heart, nothing of course will – this story could also be transported into the year 2225 and would likely read in a very similar way. So if you can put up with Emma’s obnoxious ways, you should meet in the pages.

Like you, I read this as part of a group readalong online. I needed company to keep moving through it, and I was glad to have read it, in the end. Unlike you, I don’t think Emma was mentally ill; I think she had limited choices to begin with, and then she made some decisions that limited her choices even more. Which led to a lot of unhappiness. Making irrational or short-sighted decisions can happen with or without a diagnosis, and I think this is what actually keeps the story relevant, keeps people reading all these years later…because even though we don’t like where Emma’s headed, we can relate to parts of it. You did mention this spring that you noticed it had been a long time since you read a classic: you sure picked a tough one to readopt the habit! heheh

right? I’m proud of myself for doing it. Yes I seem to be alone in my mental illness diagnosis, but I just couldn’t help thinking ‘this woman is crazy’ the entire way through. But very true that this book remains so relevant, even today!