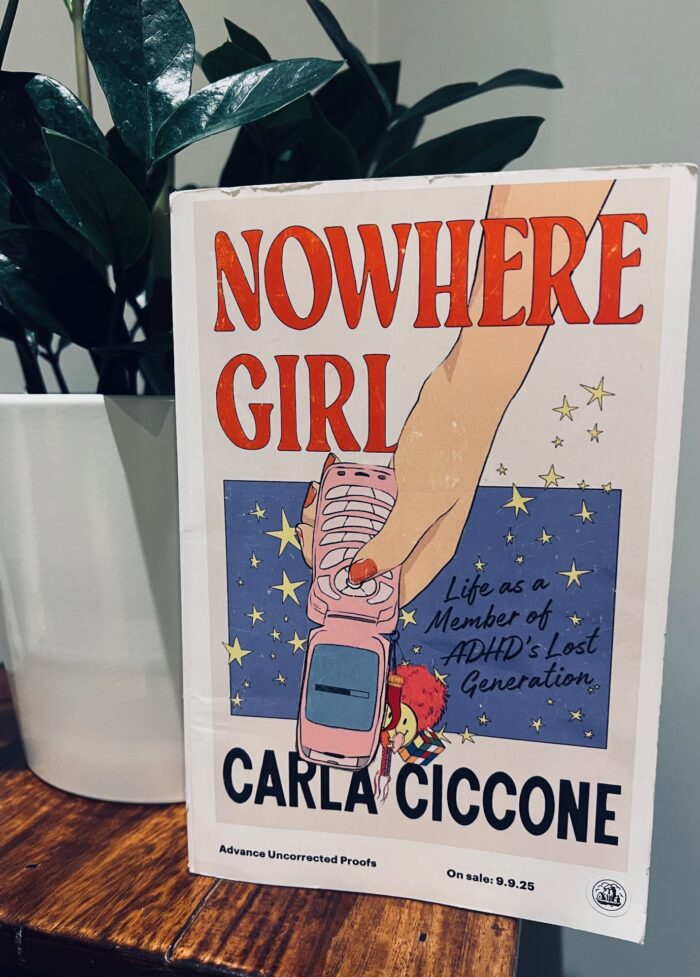

Book Review: Nowhere Girl by Carla Ciccone

This past summer I was visiting the beautiful offices of Penguin Random House Canada in Toronto, and a publicist had pitched Nowhere Girl, Life as a Member of ADHD’s Lost Generation by Carla Ciccone to me. It was an interesting memoir because it was attached to this emerging diagnosis that women in their 30s, 40s and beyond were receiving for the first time: ADHD. Many people, including myself assumed this was a diagnosis often given to young rambunctious children who can’t sit still in school, but as Ciccone argues (along with recent, scientifically proven research) that ADHD presents itself very differently in men and women, and historically, women have been struggling with this undiagnosed problem until very recently.

Book Summary

This is a memoir first and foremost, so Ciccone tells the story of her life beginning with a fairly average childhood of growing up in Canada. Her ADHD diagnosis comes at the age of 39, a few years after having her daughter. The author’s life is peppered with the relatable challenges of growing up including bullying, having difficulties with school, and a general fear of adulthood. But the chaos of her internal life, and the vitriolic inner dialogue she has with herself is what sets this apart from the typical ‘coming of age’ story. Depression plays a major part in this, and luckily she is diagnosed with that earlier than the ADHD, and finds some medication that seems to help, although once she finally receives her ADHD diagnosis, this triggers an emotional analysis of her life up until that point, realizing that her own personality traits she once despised may not have been simply a product of her laziness or disorganization, as she previously thought. For the purposes of this story she interviews other women known as “Nowhere Girls”, those who also received a later-in-life ADHD diagnosis, finding a community of people who can relate to her previous self-loathing, together realizing that their struggles are similar, and not just due to a lack of self-discipline, as they had previously been told. This is a ‘reported’ memoir, which is a term new to me, but basically means that the narrative also includes quoted research, and this book definitely has loads of facts that back up Ciccone’s claims and personal experiences. A few prominent researchers in the ADHD field are quoted throughout, and numerous studies are cited as well.

My Thoughts

As a freelance journalist, it’s obvious that Ciccone has done her research, and done it well. The notes and references to the surveys and research she cites are well laid out, and she does an incredible job of lacing these factual notes in with her life story. She touches upon certain memories in her youth that were clearly milestones for her, both positive and negative, including a childhood trauma that shapes the way she relates to others’ judgement for years afterwards. But now that she has this ADHD diagnosis, she looks at these events through this different, more informed lens, helping her process what she previously believed to be simply her own shortcomings. My only complaint with this pattern of connecting her every problem and ADHD trait was that it began to sound like every little issue she had could be traced back to ADHD, which can get repetitive for the reader. It seemed as though every challenge could somehow be linked back to her ADHD diagnosis, when in many cases lots of people experience the same thing and they simply call it ‘life’. But I realize how cynical this sounds, and it’s unfair of me to point out this out when the entire point of the book is looking back at one’s life with a new medical perspective, but I’ll admit to rolling my eyes at some parts because of this.

Gender is of course another major topic in this book, and she spends much time comparing herself as a young girl to the young boys in her school who would have immediately received an ADHD diagnosis; she didn’t have any trouble sitting still in class, so no one ever thought that her difficulty focusing could be anything but a lack of self discipline. Ciccone internalized this message of laziness and became her own worst critic, punishing herself with harmful self-talk and pushing through pain when she felt she wasn’t measuring up, which became even worse when Ciccone had a daughter of her own.

“In pursuit of the perfection demanded of women and mothers, my mom was always hardest on herself. She was my first model for the seemingly automatic self-blame many girls and women use to motivate themselves. She didn’t do this on purpose. Mothers hand down the hellish act of self-criticism to their daughters by talking about themselves with the judgement the world expects from them. The patriarchy sets us up to hate ourselves and laughs as we unwittingly train our daughters to do the same. For my mom, being good meant self-sacrifice” (p. 67 of Nowhere Girls by Carla Ciccone, ARC edition).

I think this pursuit of perfection is a very common thread for women, whether we are mothers or not. My first instinct is to blame myself because I feel as though my drive comes from within, although perhaps this is the point Ciccone is making – society’s expectations of women are so pervasive, this drive for perfection feels like it comes from within because we’ve completely internalized it. I’m interested to hear what other people think (men and women!) in the comments below. Either about this book, or the gender expectations around behaviour. Talk at me!