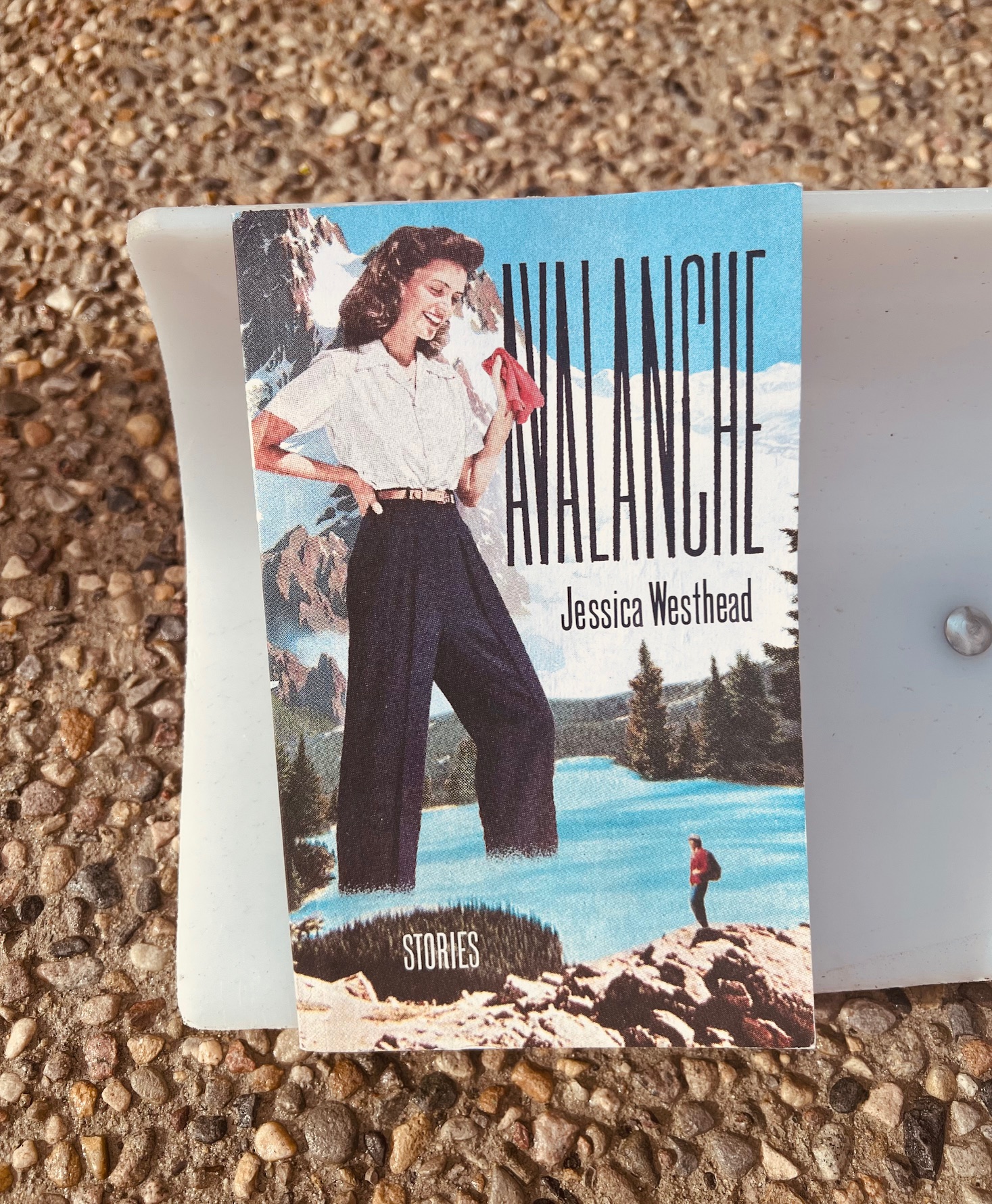

Book Review: Avalanche by Jessica Westhead

Have you ever read a book and cringed, because you recognize bits of yourself in a character, but that character is clearly doing the wrong thing? I had this unfortunate experience when reading Avalanche by Jessica Westhead; a short story collection all about white ladies who are trying to be politically correct, but end up saying and doing cringe-worthy things in the process. Now I know what you are thinking – why would I want to read a book that embarrasses me? And my answer is – why not? The older I get, the less seriously I take myself, and this book showed me how important it is to a) keep learning and b) laugh at myself more.

Book Summary

In just under 150 pages, Avalanche contains 16 short stories, most of them being around the same length. Each story is written in the first person, so we hear and understand what the protagonist is thinking versus what they are saying. Each story is also written in the voice of a white person (and notably, the author is white herself). Most are written from the perspective of a woman who is, in her own mind, being helpful or kind. “How We Challenge Ourselves” is perhaps the one exception to this. It’s written from the perspective of a white man who is defending the accusation that his sport, the triathlon, isn’t diverse enough after a friend of his sent him an article that analyzes who does and doesn’t participate in triathlons. This particular narrator verges on a violent anger when something he considers so wonderful could be criticized. Small examples of defensiveness come up in other stories too; in “The Meeting” a mother claims that she doesn’t care about people’s differences, and no one deserves a leg up. But the majority of the characters aren’t defensive or aggressive, they’re mostly just clueless. In the hilariously titled “Gary How Does a Contact Form Work Do I Just Type in Here and Then Press Send and That’s It?” a woman is sending a blogger a note about her Caribbean Style Chickpea Curry recipe, thanking her for including a picture of herself to ensure readers knew the recipe would be ‘authentic’. After a couple mentions of how beautiful her hair is and how exotic she is, she ends the note with a couple of smiley faces. Most of these women aren’t outwardly harming anyone, but their ignorance and lack of self-awareness does grate after awhile, which is clearly the point Westhead is trying to make.

My Thoughts

There is no denying that some of the characters in this book are simply obnoxious. There is a range of behaviour exhibited in these stories; from harmless but annoying, to defensive and purposefully hurtful. It was the women who were trying to distinguish themselves from who they deemed to be ‘offensive’ where I recognized myself most, and I think that’s where many people many sheepishly recognize their behaviour or inner dialogue as needing room for improvement. Most of the female narrators approached the issue of race among their other focuses in life; family obligations, parenting, jobs, the challenges of marriage, so it’s understandable why saying or doing the right thing isn’t always top of mind in their busy lives. In the title story, a mother is preparing protest signs for her and her daughter to carry in the Women’s March, eager to demonstrate to her child how progressive she is. But in the meantime, it’s clear she is stuck in a misogynistic marriage, tiptoeing around her husband, afraid to voice her opinions around him, and basically stuck in a modern-day servitude.

Why would an author write a book that focuses on pointing out the hypocrisies of others? It may seem like she wrote this to shame others, however I don’t believe that’s the case. Instead, I think she’s hopeful that people may recognize the range of ways in which we can discriminate or ‘virtue signal’, and try to change their actions and conversations accordingly. Many of my peers (myself included) have good intentions, yet this isn’t always good enough. Simply remaining open to learning and doing better is all we can ask of ourselves and each other, and I believe this is the true intention of the author and her short stories. Humour also helps this self-reflection go down a bit easier, as many of the stories and situations are entertaining, especially when the reader is so clearly ‘in on the joke’

Now here is where opinions of those who follow my blog will likely diverge – the idea that we do need to change how we talk is a fairly new and progressive one, and I know for a fact that many people think we simply don’t need to change, or that we’ve done enough. But I’ve been raised in an environment that prizes education and the need for constant improvement, so as western society shifts into a more inclusive one, I’m eager to change along with it. There is no clear ‘ you should do this, and not that’ kind of message in this book, but Westhead’s examination of these behaviors should be enough to get us all thinking of the positive changes we can make to our dialogue – both our inside and outside voices.

It can be hard to know where, or from whom, we should learn. I’m slowly realizing that studying culture in particular may be the best place. Culture shows us what is normal and how some cultures have developed out of shared trauma. For example, people in both Deaf American culture and Black American culture have histories of specific kinds of violence and oppression done to them, which demonstrates why they may not be trusting or find something another culture thinks it as simple (e.g. “I love your hair!”) to be offensive. When one person says that a person from another culture is being too sensitive, what they really mean is they don’t share the same experience, history, or norms.

That’s a very good point Melanie. And that’s always what this comes down to, isn’t it? Understanding that others come from a different experience, shaped by different pasts, beliefs, etc. I’ll always be supportive of those of us who are simply trying to ‘do better’ and be more understanding towards others. Some people may roll their eyes at this, but I don’t see the harm in trying to meet people where they are at, wherever that might be.

I’ve followed Westhead’s writing since her first book and am always interested to see what she’s writing next. My sense is that there’s always at least a small part of her in the characters she creates and explores. They’re always empathetically drawn, even if they’re not exactly relatable or likeable per se.

In your final thoughts, you seem to be saying that it’s a modern trend, this idea of whether to be open-minded about the idea that how we say/offer things doesn’t mean it’s how other people hear/receive things? But hasn’t that been the case for as long as there have been people? Or does the collection have a kind of ripped-from-the-headlines feel to it, that eludes to more recent events specifically? I guess maybe I’ll have to read it then, sooner rather than later. heheh

It’s a good point you bring up Marcie. Now I have to go back and read my own review!

It feels like Westhead is trying to point to very timely situations, however what she is truly discussing, is really something that has been happening ever since there were people, and language!

Sounds like an interesting balance to strike: I’m more curious than ever about her latest book now!

It’s definitely a unique one!