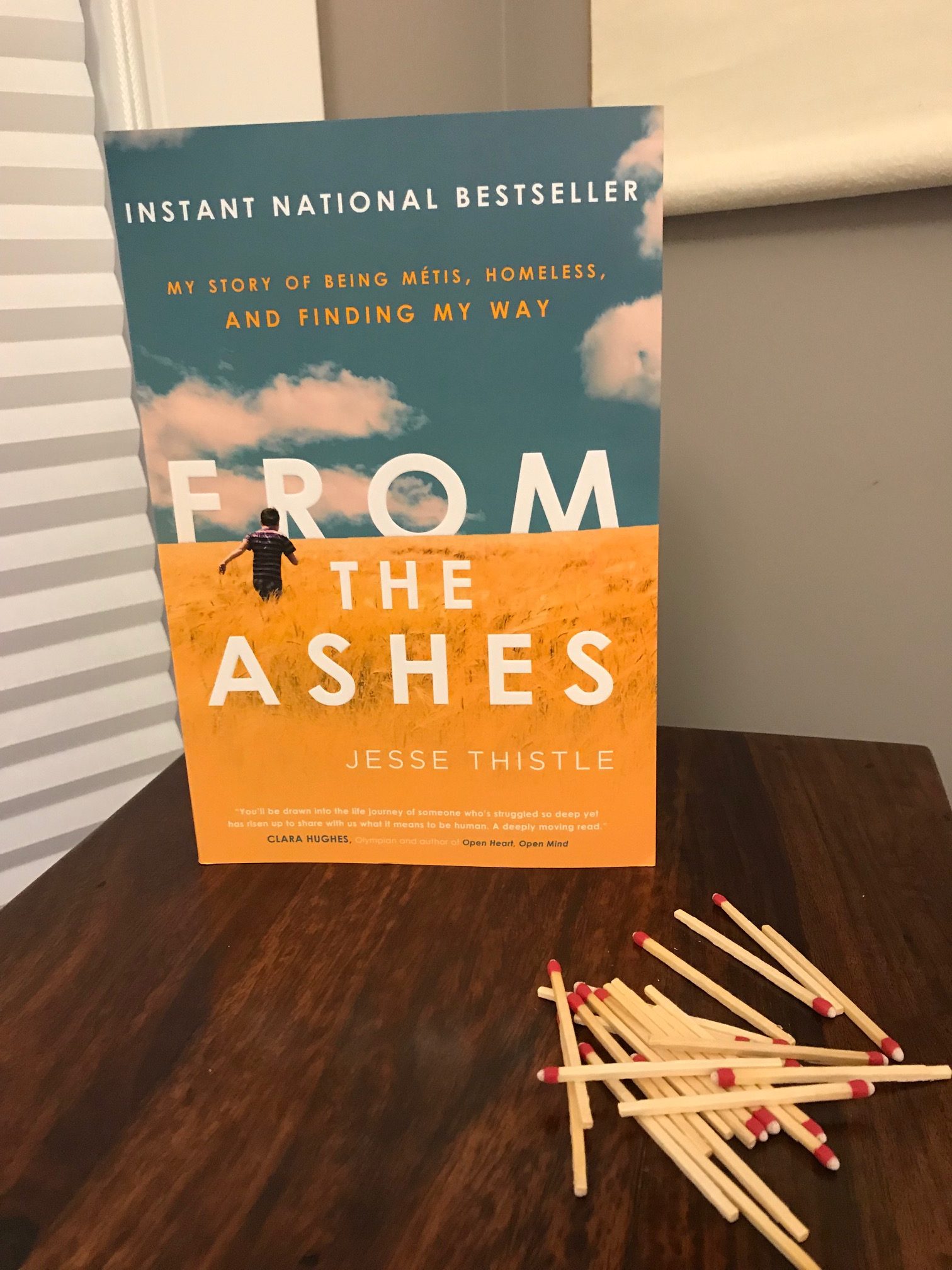

Book Review: From the Ashes by Jesse Thistle

You know how people joke they are addicted to something? I regularly claim I’m addicted to chocolate, and those of you who know me well know this is a fairly accurate statement. I almost always have it in the house, and when I go a full day without having any of it (which is rare in itself) I’m always a bit disappointed. So I suppose that isn’t a true addiction in every sense of the word if I can go a few days without it, however I think we’ve all felt that ‘pull’ for something at one point in our lives. But what if you were actually addicted to something, can you imagine the havoc it would wreak on your life? I couldn’t. And I’m thankful I haven’t had the experience, but just because I’ve never been affected by it doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist, or those who suffer from it are just ‘weak’ and I’m strong. From the Ashes by Jesse Thistle is a harrowing depiction of addiction and its power over our mind and bodies. Luckily this is also an uplifting read, because Thistle tackles his addiction and wins, ultimately becoming an award-winning scholar, using his platform to raise awareness of various social issues.

Thistle is Métis-Cree-Scot, but he didn’t always understand or even recognize his heritage. As a young child, he was subjected to all sorts of trauma; witnessing his father do drugs in their home, starving for days at a time with no parents or adults around, and eventually ending up in an abusive foster care home with only his older brothers for protection. Luckily, he is adopted by his grandparents along with his brothers, so he enters a relative period of stability. Unfortunately he falls into a life of petty crime and drugs while in high school, susceptible to the addictions that haunted his estranged father. For a period of almost 11 years, Thistle is homeless and addicted to various drugs. Held hostage by his unrelenting need to get high, he hurts those close to him, slowly isolating himself more and more until he is truly alone. Once he finds himself back in jail, he meets some people who encourage him to finish his high school education while serving his time, and the hopeful beacon of education slowly opens a new door for him, eventually motivating him to try rehab a second time, and successfully completing it.

I realize I’ve described this book in a very ‘boy makes good’ sort of way, and it may come across as a bit cliche. But Thistle’s story is an important one, and the addition of his Metis heritage and the inner turmoil it causes him forces readers to look at his problems through a very distinct lense. He has very early memories of collecting Saskatoon berries with his Kokum (grandmother), and occasionally sees his extended family at various gatherings, but he’s never really told what being Metis means until he’s much older and shows a genuine interest. Like many indigenous people in Canada (and abroad), Thistle was subjected to racist comments and taunts as a young boy at school, so to help deflect attention away from himself, he tells other students he’s Italian. He’s embarrassed by his looks, and he’s embarrassed by his poor grades and inability to focus, so when drugs offer him a way to be included and in control, he jumps at the chance. Of course many people are faced with these same conditions and don’t fall into addiction, but Thistle has so many cards stacked against him at this point, it’s easy to understand why he keeps making bad decisions. Despite his difficult circumstances, he does not blame anyone for his problems, he fully concedes he makes the wrong choices, and it isn’t until he starts making different decisions that his life turns around.

Because he was homeless for so long, clawing his way back to a normal life forced him to re-learn things that I found surprising. So often we minimize the struggles of homeless people; ‘why don’t they just get a job?’ as we pretend to not see their outstretched hand on a street corner. But once they are given a leg up, and even if they’ve detoxed their way out of rehab, the challenges they face are hard to imagine for those of us living independently. Towards the end of the book, Thistle is filling in his university application and his girlfriend Lucie leaves him to complete it on his own, which he struggles mightily with, but feels so accomplished once he does it:

“Since living with her, Lucie had helped me fill in health card forms and taught me how to drive and how to fill in all the car driver insurance forms…Lucie basically taught me how to access society again (p. 321 of ARC). “

Thistle had been in school for many years before he dropped out, so how do you forget how to fill out a form? It’s something so many of us take for granted, but if you’re completely alone, and haven’t written a single sentence in years, how do you navigate these basic expectations of being an adult in a first world country?

Ultimately, this book is a lesson in empathy. His story is one with a happy ending, but he acknowledges how easily he could have remained where he was, or worse, dead from an overdose. In the epilogue, he revisits one of the areas he used to score drugs at the very end of the book, recognizing someone from years ago. His old friend doesn’t know it’s him at first because Thistle’s clearly well-fed and sober, but he eventually recognizes him and they exchange a few pleasantries. As Thistle walks away from that encounter, he realizes how far he’s come, and how ‘done’ he is with that life. Lucky for us too, because he is not only a beacon of hope and wisdom for those with similar problems, but a generous citizen who is directing his time and efforts to help us understand how we can best deal with the struggles of the homeless and addicted.

At the library, we have training on how to best serve and work with homeless patrons. One thing that surprised me is that most of us can think about the future — next week, next year, next five years, etc. Homeless people, however, tend to only have a 24-hour window looking forward, meaning consequences have little effect on them.

That is suprising actually, thank you for that. What an important thing to keep in mind when interacting with them!!! That sounds like really useful education and training that everyone should have really

Knowing from personal experience how hard it is to give up smoking I’ve always had a huge amount of sympathy for people fighting addiction of any kind and admiration for those who succeed. Good on him for turning his life around!

you used to smoke FF? Wow interesting. Good on ya for quitting, no doubt that was intense.

Sounds like a very moving book. Anyone can become an addict, and I have hope that we are moving towards a destigmatization of addiction.

me too! I think with the opioid crisis, we are hopefully moving towards a broader understanding of addiction…

I have a close family member who is an addict, and even though it’s an awful thing, it has also helped me understand things I might not have otherwise. It’s also helped me to not be so quick to judge others – it can happen to anyone.

Great review!

That’s a tough situation Naomi, but you’re right in that it completely changes our viewpoint of addicts. If only people tried to be more understanding, I think we could do alot to get rid of the stigma…

I had a hard time with this book: too much “ashes” and not enough “from the”. He just writes about one occurance after another with no self-reflection. He never talks about being lonely or angry or what made him change. Maybe I’m prejudiced because I’ve been through all this already with my daughter and she has a PhD now. Addiction stories are hard to read for people who have lived through having a loved one with addiction so maybe that’s why I didn’t like it. Maybe addicts have no capacity for self-reflection?

I know what you mean-I was hoping for more stories about him sober, but maybe he still needs time to reflect on that part of his journey. Perhaps a sequel is coming?