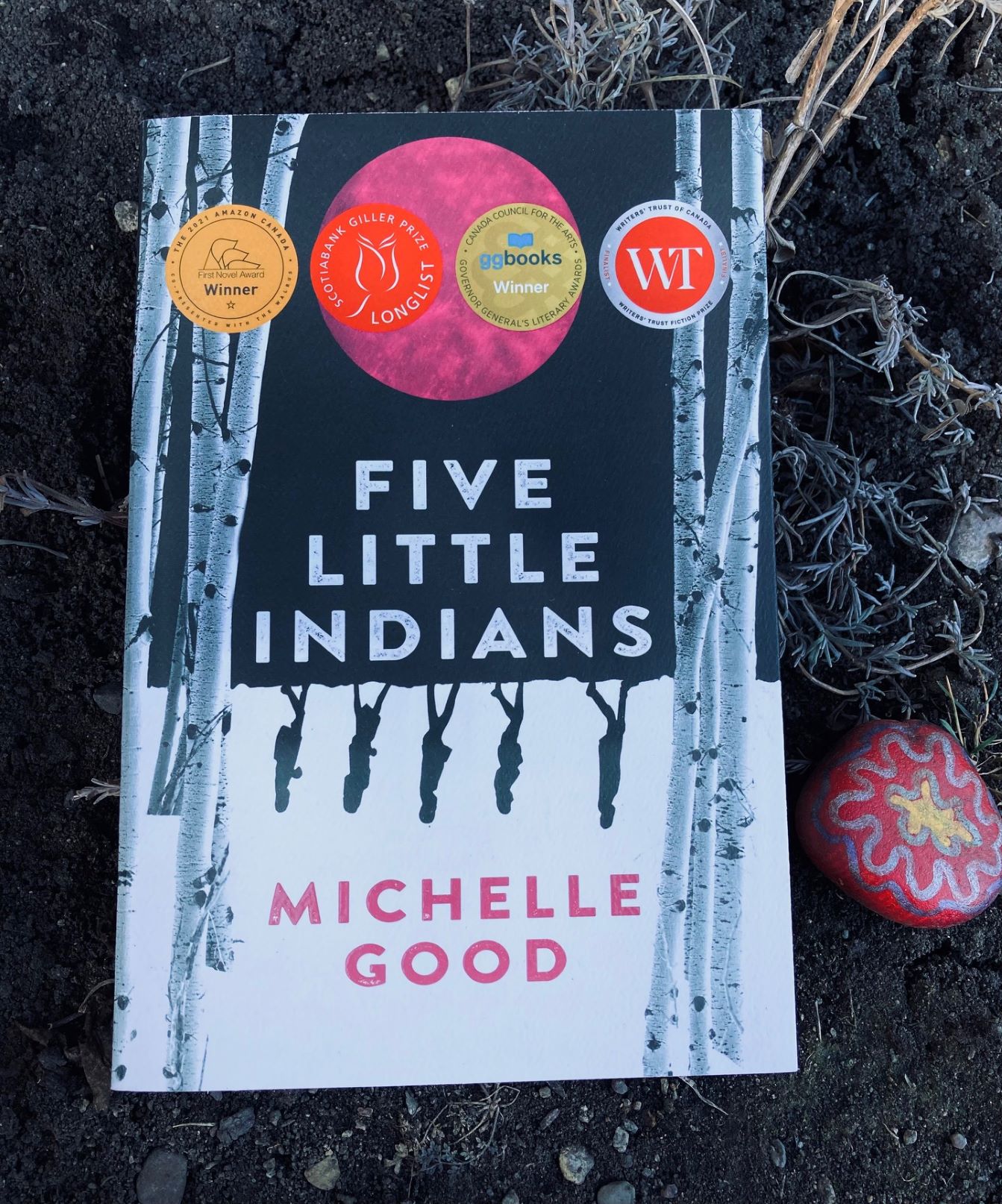

Book Review: Five Little Indians by Michelle Good

I won’t say my reading is influenced by awards, because it rarely is – quite often, my book choices depend on the themes I’ve come up with for my monthly radio segment, and the books that land on my doorstep for review. But every so often I break out of this pattern and pick up a classic book that I’ve been dying to read, or in this case, a book that’s won so many awards, it feels simply wrong to have not read it by now. Five Little Indians by Michelle Good has been nominated or won virtually every Canadian literary award possible, and just last week won the the Canada Reads competition. Not only that, my followers on social media have insisted this book is a must-read, so I finally purchased a copy a few weeks ago and read it over the course of three days. Not surprisingly I loved it, but I can’t say I was shocked by any of its contents, as someone who has been reading Indigenous literature for years, it included things I’ve been well aware of for over a decade.

Plot Summary

Kenny, Lucy, Clara, Howie and Maisie are Indigenous children taken away from their parents, and forced into an isolated residential school on the coast of British Columbia in the late 1960s. We spend a brief period of time with them while at the school, learning how they either escaped, or aged out of it, but the majority of the book focuses on their time as adults, most of them living in the seedy Eastside of Vancouver. The narrative follows each character separately, weaving in and out of their lives, not always in a linear fashion. Their paths do cross again, each sharing a version of trauma that most don’t understand, even other Indigenous people who were spared from the residential school experience. Because these characters attended residential school in the 60s and 70s its easy to dismiss this as a long ago problem, but I will remind my readers that the last residential school didn’t close in Canada until 1996, so unfortunately the trauma these schools inflicted on people are still very much in the present for many people.

My Thoughts

Mercifully, the book does not spend too much time in the residential school, the kids are ‘out’ of it fairly close to the beginning of the book, but I include the word in quotations because sadly, they can never really escape what was done to them there. The beatings, rapes, tortures, and deaths of some of their classmates continue to haunt these people, and the affects of this psychological trauma is released in each character differently, as well as their families. Despite all this darkness, what makes this book so successful is its ability to create such relatable and loving characters within these horrific circumstances. As a reader we may not be able to relate to this pain, but we understand their actions in relation to it – drug use, suicide, alcohol use, these destructive acts take on a whole new meaning when considering what came before them.

I was lucky enough to participate in an informational session a few weeks ago with a local elder here in Calgary, who is a social worker that specializes in helping people who have been traumatized. Many will be familiar with the term intergenerational trauma by now, but what was fascinating to hear her speak about was the fact that there is now brain-science to back up this term – so when people say ‘why don’t they just get over it?’ we now have a scientific explanation as to why that is so difficult. Many people have pointed to this book as a clear explanation of why ‘they can’t just get over it’, and like I said above, I’ve been aware of the horrors of residential school for awhile because I took an Indigenous literature course in university where this was explained to me, but many Canadians were unaware of residential schools until last year when the children’s bodies were discovered on those properties. Those feelings of anger from the Indigenous community also came from the fact that only now were people believing and understanding them – they’ve known bodies were there for years, but it’s only coming to light now – and this book also deals with the delicate excavation of those missing children’s bodies.

I’ll try to bring this post back to an actual review, rather than just a personal rant of mine. The characterization in this novel is what sets it apart from other works that delve into similar tragedies. Through these five people, we are shown the horror, struggles, and potential for joy in their lives. They aren’t just symbols, they are people that have been lovingly drawn for us readers, and their humanity is what makes this book so emotionally effecting and compelling. So often residential school survivors are shown as statistics, but this book does them justice, and reminds us of the child behind each one of those bleak numbers.

Great review. Like you, the content here wasn’t new to me when I read it but I still think it’s so important to keep listening to and highlighting these stories. I thought the portrayal of the daughter (can’t remember her name) toward the end was also really good at demonstrating how these traumas travel through generations and are still very present even amongst younger people who weren’t in the schools.

Gosh I can’t remember her name now either but i know exactly what you are talking about – yes this book is useful to Canadians (and others) in so many ways

Sounds like a powerful read! I’ve mostly become aware of this issue from blogs like yours and Karissa’s highlighting books about it, although recently there has been more international coverage because of the finding of the bodies. It’s always a surprise to me how recently these things stopped – frightening, and makes you wonder what we’re doing now that we’re unaware of, in the way most people were unaware of the truth about residential schools back then.

I’m going to have to check this out!

It’s a challenging one Laila, but really beautiful too

yes it is a dark thought – what is going to come out in a few years/decades that we were just ignorant to now?

I saw on the news that the Pope just formally apologized on behalf of the Catholic Church for the residential schools in Canada. I wonder if that means anything to the affected community.

Yes that was a big deal – I think it does mean something, they have been waiting for it for awhile – the CDN gov’t apologized, but they were waiting for the catholics to do it too – all good steps toward reconciliation!

Honestly, I think I don’t know much about forgiveness in general. Basically, I don’t want someone I love to be upset, so if I’m past it, we’re over it. Or, they can walk it back and say they didn’t mean what they said or did. But to apologize for decades ago confuses me. Okay, I think I’m being too me-centric. It’s not about me, it’s about how the Indigenous community feels.

Hearing “Why don’t they just get over it?” makes me SOO mad.

What I thought this book did really well is *show* the effects of residential schools. It puts a human face on a bunch of statistics we hear in the news.

It broke my heart that their homes were no longer as they remembered them when they finally got out of school.

Yes I remember that was one of the most devastating parts – returning to a broken home from a broken place.