Book Review: Wenjack by Joseph Boyden

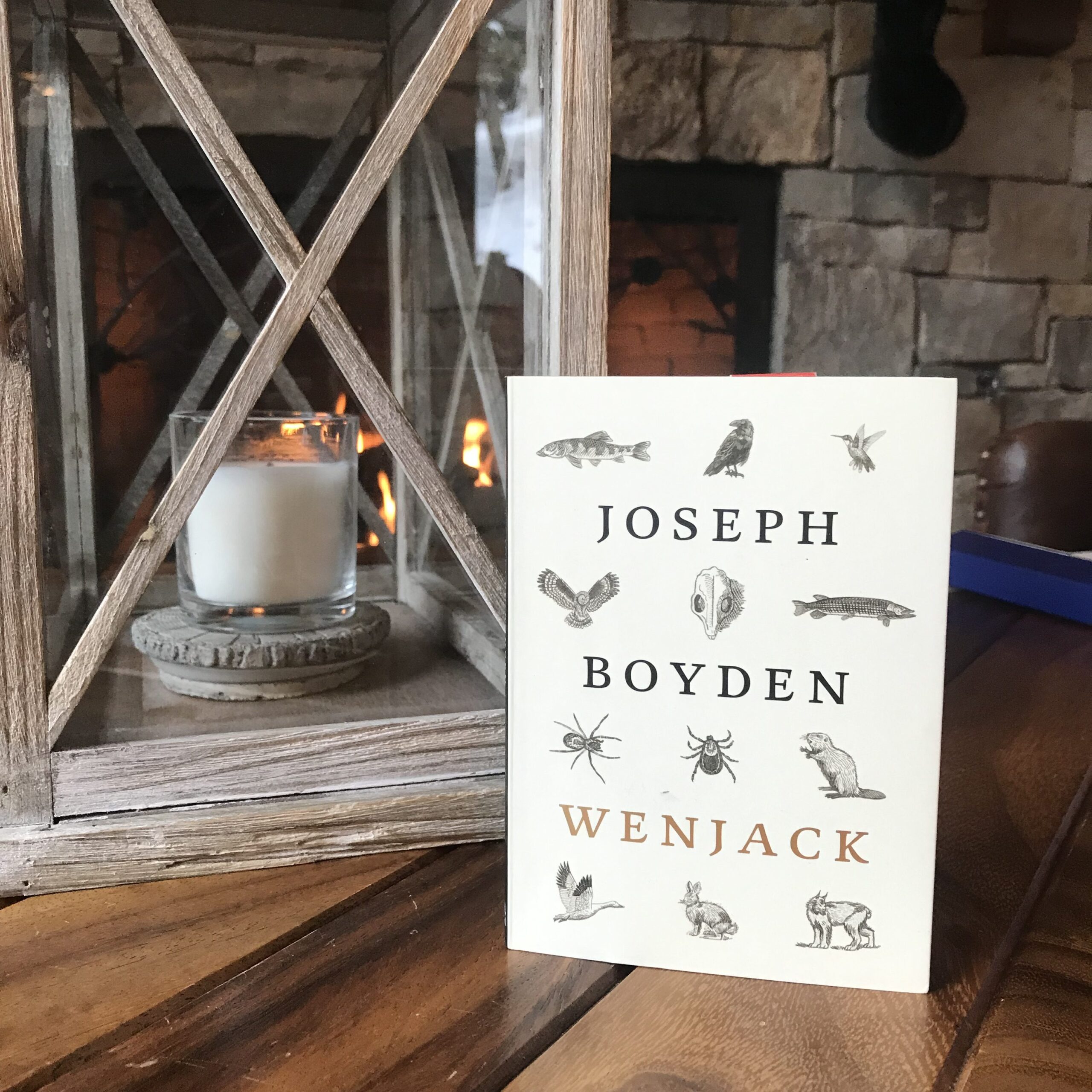

I received Wenjack by Joseph Boyden as a gift a few years ago, and have been meaning to read it since then. Considering it’s so short (102 pages), it’s a shame it has taken me so long to get to it because it’s a very well written novella and beautifully packaged to boot. Regardless of the politics around Boyden’s heritage, he’s a gifted writer, and Wenjack is worth your time.

Wenjack is written from many different perspectives. First and foremost it’s written from Chanie Wenjack‘s view who the story centers on, and keep in mind this book is based on a true story. Chanie ran away from residential school with two other boys on a fall day, wanting to return home and escape the torturous conditions they endured at school. Unfortunately, after a few days in the bush he succumbed to exposure, dying on a set of railroad tracks which he believed would lead him home. He was not aware that he was hundreds of miles from home, which is why he attempted the escape in the first place.

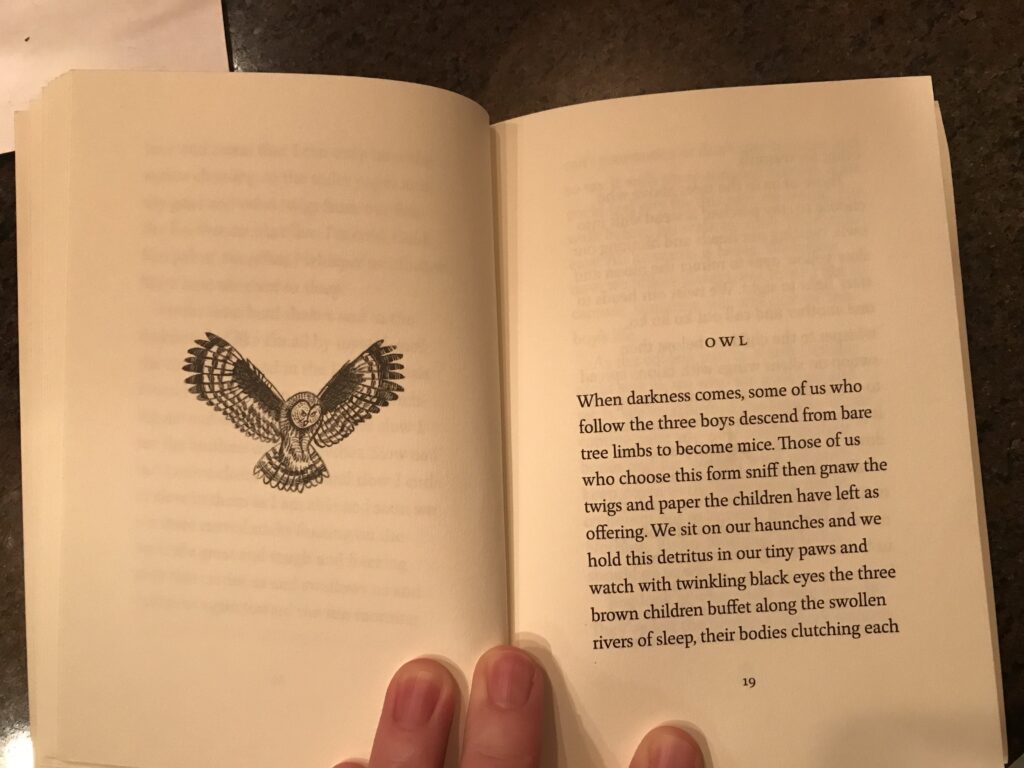

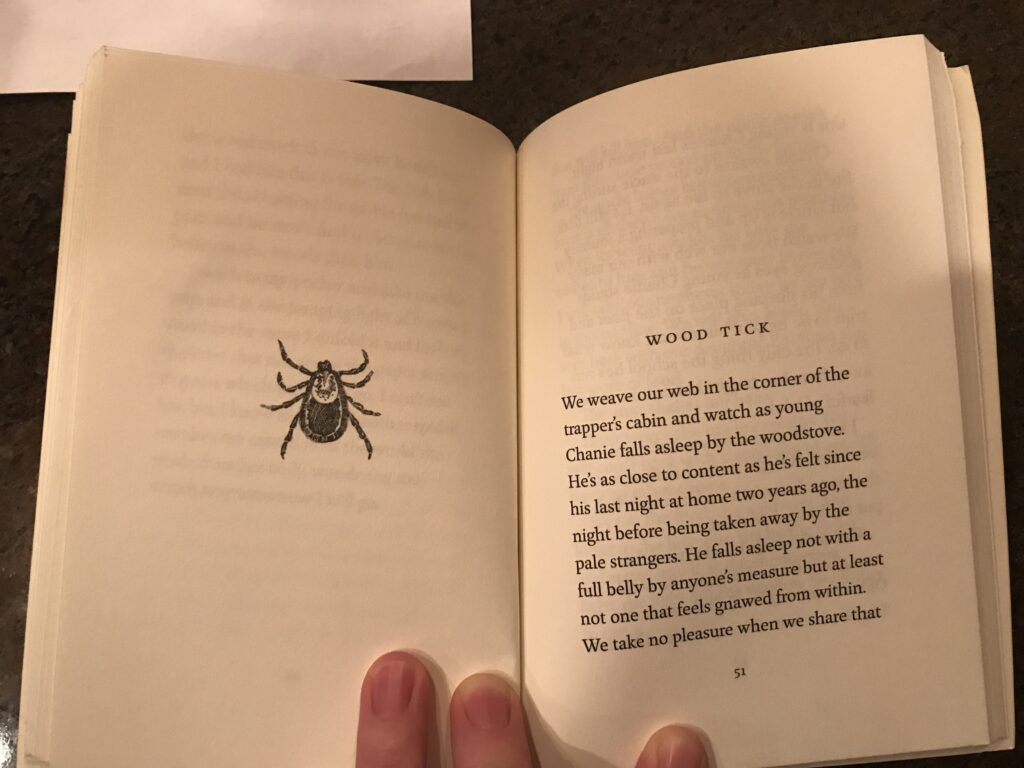

Obviously, this is a painful story to read, especially because you know Chanie will be dead by the end of the book. What makes this work so compelling is the alternative voices of the animals that witness his final days, creating a narrative that is rich with spiritual imagery mixed with the natural environment that surrounds all the characters in the book. It creates an interesting dichotomy too; nature is where Chanie feels safest, away from the abuses of the school he has fled, but it is also nature that kills him, although there is plenty of foreshadowing to indicate that Chanie’s spirit died years ago when he was originally forced into the school by the government, against his family’s wishes.

As I mentioned above, the book is gorgeous. At the beginning of each chapter is an illustration of the creature ‘featured’ in that section, whether it be words written in the perspective of that animal/insect, or something that Chanie takes note of during his journey. The pictures are drawn by Kent Monkman.

For those who want to learn more about residential schools and the terrible impact it has had on Canada’s indigenous population, I would highly recommend this book. I know many people don’t feel ready to read a work of non-fiction on the subject because it can be quite painful, or act as a trigger for victims who have also experienced abuse, so this short work of fiction (but still based on a real boy) is an easier way to introduce oneself to the issue. The gentle weaving of nature throughout makes it less painful, but we are still forced to witness the horror of what the schools have done, which is important for us to acknowledge, again and again.

The summer after my freshman year of college I took a seminar. The focus was writers in the U.S. and the time period wasn’t super old. Maybe Emancipation Proclamation and forward? Anyway, I remember a whole section about indigenous children being sent to school, losing their language, being torn away from their parents….and it just blew my mind. I had never heard of such a thing happening. I had always learned about white immigrants who came to the country and forced tribes off their own land through “relocation” programs or straight up murder, but taking away children and sending them to schools was WAY more recent than I had thought possible.

it’s crazy-the last residential school in canada closed in 1996!!!!

Whaaaaaat. Where was that?

I believe it was northern ontario? Pretty horrifying stuff.

This is so hard! Obviously Chanie’s story is such an important one and deserves to be told. On the other hand, the politics behind Joseph Boyden’s heritage mean that I can’t read his version. Storytelling is so sacred within Indigenous culture that it feels wrong to me to read a version of an Indigenous story from someone who tried to co-opt that heritage without experiencing the burdens of that culture. You know?

It sucks because I’ve heard wonderful things about this book, like here, but I can’t separate the story from its creator.

Yes, I totally know what you mean. But I counter you with this-what about Gord Downey? He tells stories with his music and he isn’t indigenous. And I must admit I am completely stealing this argument from another commenter LOL

There is a HUGE difference between Gord Downie and Boyden! Boyden pretended to BE Indigenous and then used that identity to build a career without having to live through any of the experiences he exploited. Gord Downie used his platform to amplify Indigenous voices, he worked WITH Indigenous groups to tell their stories. He never claimed ownership. He worked for reconciliation, taking responsibility for the harm that white people have done to Indigenous communities.

Yes that’s a good point (and i love Gord Downie, so I’m in agreement that his work is valid and well-intentioned) but I don’t think it’s fair to discount what Boyden has done either. It’s not right that he lied about his heritage (or the murkiness of it) but his writing is still really good. And although it’s unfair he’s taken up the little room allocated to native stories, he’s stepped back since then to make room for these previously unheard voices. And the attention his writing received in the past shone new light on aboriginal stories in general which drew much needed attention to this part of our nation’s literature. I’m not necessarily defending his actions, but I don’t want to discount his writing because of it.

So what you are saying a human being can only write for his/her/their own race or gender?

My friend Kenard Martin a former Tarheel in football, pro in Canada now a Munster. He gave me multiple books to read and autobiographies of African leaders.

One very important book was on the subject of understanding the “black experience” and various insights beyond any other person or book.

I will not tell you who the author was or book title because he is white.

This was such a powerful read and such an important story to be reminded of in our country’s history.

What a bee-yoo-tee-ful picture, Anne!

In every event I have ever heard Joseph Boyden speak at, going back to Three Day Road days, he always itemized his heritage like a menu: the indigenous stuff in there with all the rest.

I think a lot of readers/media-folk simply latched onto the idea that he was the spokes-person for indigenous writers, over the years, as much as he inhabited that position. That whole reduce-to-simplest terms tendency.

It was easier for a lot of Canadian rreaders to simply count him as “the indigenous writer” than it was to go looking for other indigenous writers to read.

Of course he should not have been the only voice amplifying indigenous stories, but his voice has amplified those stories, and that’s note-worthy.

Especially with the degree of craftsmanship in this volume. It’s a simple and powerful story. It took me ages to work up the courage to read it, and, then, I was sorry that I had waited so long.

Yes, I totally know what you mean. It was a lovely book wasn’t it? An important story to be told, over and over again by lots of different people.