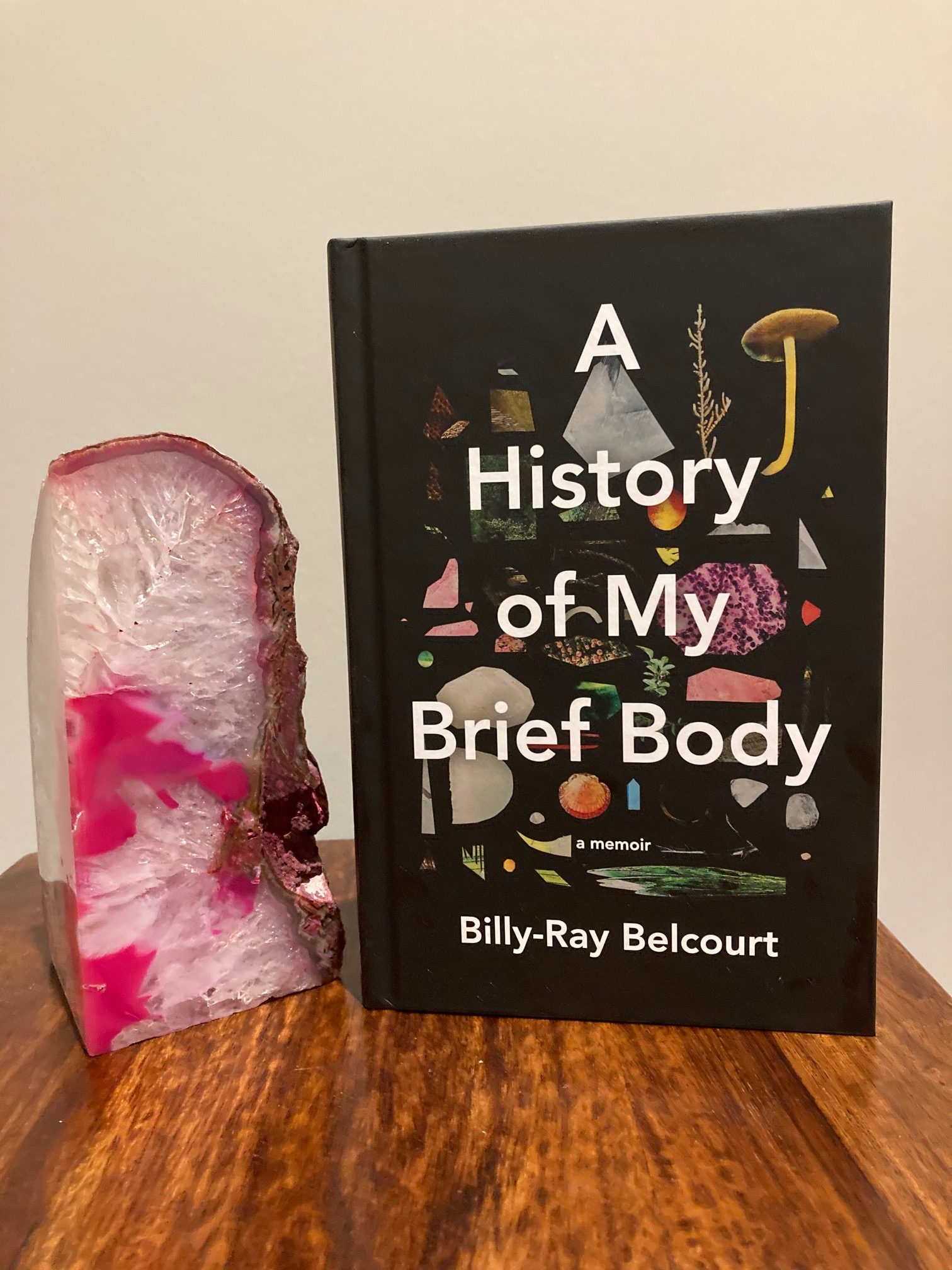

Book Review: A History of my Brief Body by Billy-Ray Belcourt

The more I read, the more eager I am for a challenge, or at the very least, the more I want to read stories that aren’t entirely straightforward or obvious. After the entertaining Harry’s Trees from last week, I headed back to my book shelf in search of a book that would push me, so I reached for A History of my Brief Body by Billy-Ray Belcourt. Having read his last poetry collection, I knew what I was getting into with this latest offering, but I’ll also admit to being sucked in by the beautiful cover, because no matter how many books you read, the cover still matters!

Book Summary

A History of my Brief Body is a memoir, but it’s an experimental one; it’s not written in chronological order, and in some cases Belcourt uses framing techniques like the alphabet to ruminate on a particular aspect of his life or viewpoint. Keep in mind too, Belcourt is also quite young, so the idea of writing a memoir at his age signals to the reader that this won’t be a typical ‘story of one’s life’. Instead. he touches on a range of things; colonial violence against the indigenous body, the experience of being queer AND indigenous, the breakdown of his romantic relationships, the way he interacts with the queer community through dating apps like Grindr, and the massive influence his kokum had on him as a young child. All of these experiences are written in a language that shifts from academic, to philosophical, to visceral. For example, he’s quite explicit when he describes some of his sexual encounters with other men, but when he hooks up with white men he often becomes poetic and introspective, commenting on the fluid nature of the power struggle that ensues when the question of race comes up between them. Hook-up culture is risky for so many reasons, but the ever-present possibility of danger is heightened when men approach Belcourt specifically because he is indigenous. This is a minefield Belcourt attempts to maneuver within, and he contextualizes these experiences by referencing Toronto’s Gay Village Murders that just recently ended with a conviction.

My Thoughts

The reason I found this book challenging is the language. Similar to Belcourt’s poetry, it’s not straightforward or linear. He often quotes from academics or philosophers which can be distracting, but he does it so seamlessly that I can’t help but admire his breadth of knowledge of various kinds of literature. He doesn’t quote these people as a way of showing off, instead, he subverts the reader’s expectation that as a gay indigenous man his experience is somehow ‘unknowable’. By quoting people who don’t necessarily look or sound like him, he is proving to us that it is possible to relate to each other, to show empathy for each other, even when our backgrounds or points of view vary widely. In the end, we’re all human, and appointing particular ideas to groups of people is unfair when we all share similar thoughts and feelings. I tend to shy away from reading philosophical works because I find them too opaque, but he mixes a pleasing amount of philosophy in with the ordinary which prevented me from becoming frustrated.

Belcourt also touches upon some timely issues that are currently at the forefront of current Canadian politics. He doesn’t hold back when identifying his anxieties and assumptions: “I have a phobia of the police. How could I trust he who disavowed personhood to instead be a gun? …to be a gun is to be against life. I want to be for life and to be against that which is against life” (p. 47). Earlier in the book he also states: “NDN boys are ideas before they are bodied. Our lives are muffled by a flurry of accusations that outrun us “(p. 14). As an indigenous man Belcourt frequently experiences acts of racism, and many assumptions are made about him simply based on his appearance. I was struck by this notion that fear affects him both ways; some fear him based on how he looks, while he fears law enforcement for the choice they’ve made to carry a gun. Do I agree that all police offices are ‘against life’ as he says? No I don’t, but I also understand his fear of them. I’m a white woman who has only been helped by the police, but if my skin was a different colour, I may feel differently. I’ve sat in a room of black Calgarians and listened to their fears of police, the misunderstandings that have occurred while they were completely innocent, in many cases simply trying to help someone in need. Sadly, I would argue that indigenous people are at the receiving end of racism here in Alberta more than black people, I am witness to it regularly, especially on places like public transit.

What I appreciate most about this book is how vulnerable Belcourt is, especially as a man, when his culture so frequently asks male counterparts to remain strong and silent in the face of trauma. He is disrupting this destructive myth and trope, peeling back the layers of his identity to show readers all the things he struggles with in his own life. In some cases it may appear as though he’s trying to speak for all queer indigenous men, but he roots his points in enough personal circumstance to avoid that misleading label. While it’s unfair to pin the onus of ‘education’ on his writing, his words take me a little further outside myself and my own experiences every time I read them, making this memoir yet another worthwhile work to engage with.

Yes, the cover still matters! And this one is beautiful! It sounds like a good book to read if you’re seeking other perspectives. Which we all should be. Great review, Anne!

Thanks Naomi!

I have yet to read anything by Belcourt but I’d like to read this one. I’m currently reading “Halfbreed” by Maria Campbell and it’s reminding me how much a personal memoir can challenge my ideas and assumptions about what life in Canada is like.

Oh that’s a classic for sure. I read it years ago in my indigenous studies course and I remember it making quite an impact on me

Yes, it’s very impactful. I’m reading the new edition that came out last year and the intro really outlines how much of an impact its had on Indigenous writing. I didn’t realize how young she was when she wrote it!

I know it’s crazy!

This book sounds amazing. The hard thing about following your blog is you often highlight these great writers who aren’t published in the U.S.! I agree that the police can be scary. I’ve had two memorable bad experiences with police, and even though I’m also white, I’m terrified of a man in power with a gun because I’m a woman. Many, many, many people are in vulnerable positions with police. But I keep my ears open for stories to reassure me that the police service, at its core, is there to help.

Yes, I hate to paint them all (the police) as the same, because there are good and bad ones, same as people of course. A story went viral here in Calgary last week where a cop was called to a grocery store because a guy ran out after taking some food off the shelves and not paying. Instead of arresting the man, the cop took him back in the store and bought him a whole cart load of groceries that they picked out together!

This book sounds very good. I definitely need and want to expand my reading of Indigenous voices.

we are so lucky to have such a rich collection of indigenous books here in Canada, and more and more are always coming out

This is on my TBR; I’m looking forward to it. But I do wonder about its presentation as a Memoir, whether that doesn’t conjure up a different set of expectations for a reader. Not that one doesn’t aspire to art as being something that does challenge our assumptions as readers, but its hard to convince people to read something that’s removed from their own experience and I wonder if identifying this as a memoir helps/hinders that. Not having read it yet, all I can do is wonder: what do you think?

It’s very different than a memoir, I found it closely linked to his book of poetry that I read before. But, I enter his work with an open mind because I know I’m going to be challenged regardless, even if I’m just struggling to figure out what’s going on LOL