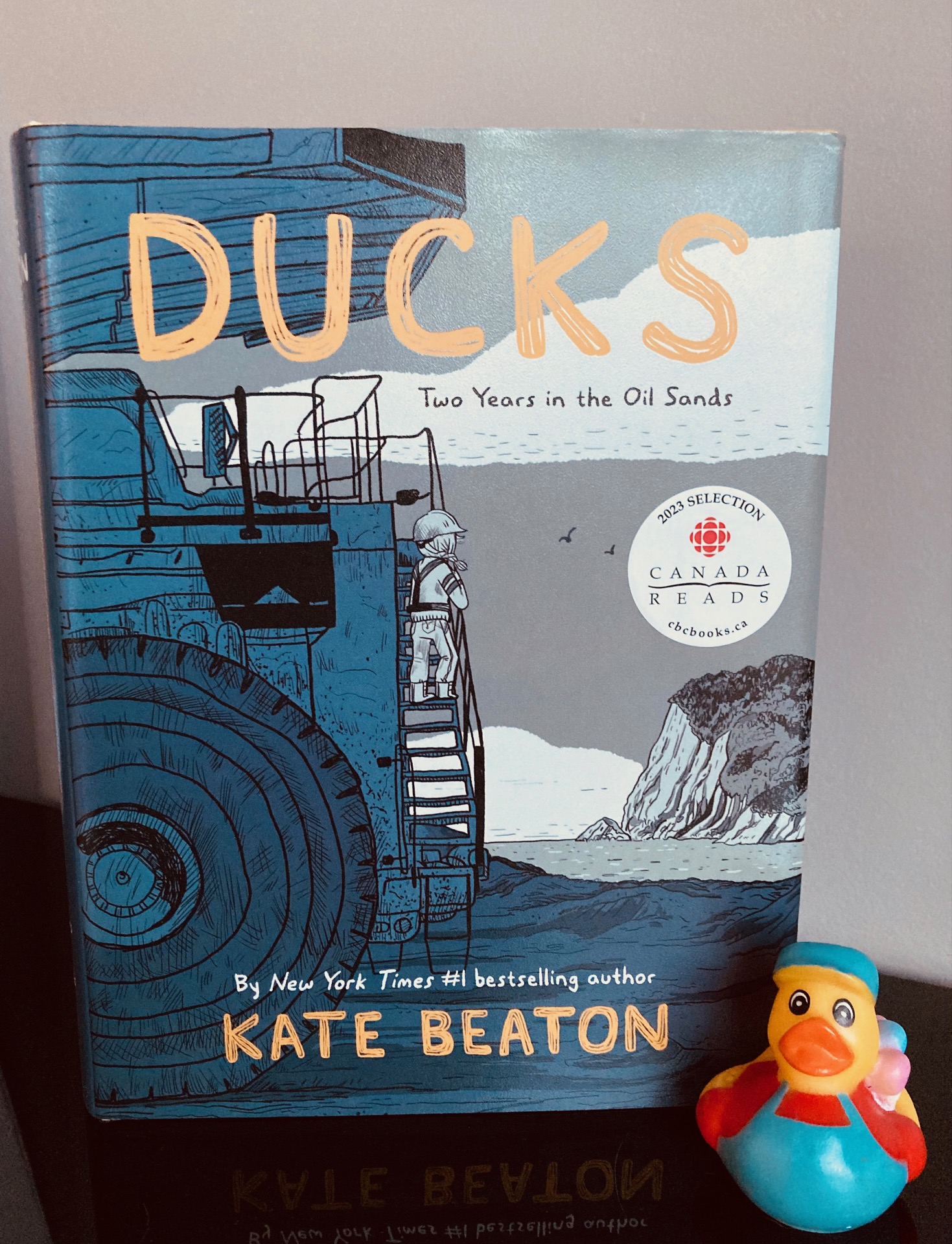

Book Review: Ducks, Two Years in the Oil Sands by Kate Beaton

I always regretted not attending this one book event; it was a snowstorm here in Calgary and no one was on the roads, so as the consummate rule follower I am, I stayed home from seeing Kate Beaton speak about her new book Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands back in 2022. I saw the pictures afterwards and it looked like an incredible event, with musical accompaniment and lots of laughter. Sigh. So ever since then I always meant to read this one, and I finally bought a copy last Fall and devoured it in three days. It’s a non-fiction full length graphic memoir that further complicates the way we view the oil sands here in Canada, and the hard-working people who spend weeks away from their life to make a living there. It’s a difficult read in many instances, but its graphic format also lays bare some of the beauty that’s rarely seen in those isolated spots.

Book Summary

Kate Beaton grew up in Mabou, Nova Scotia, a seaside town that’s known for lots of tourist attractions, but not much work opportunity. After completing a four year general arts degree, Beaton realizes she will have to leave her beloved town to find a job, and more importantly, pay off her student loans. She travels west, like many people in the east, to work in Alberta’s oil sands, which are located in the far north of the province (where I live in Calgary, we are fairly far south). There are so many people that come west for work; the east coast of Canada is known to be a beautiful place to visit, but a difficult place to make a living. Kate lives in Northern Alberta for two years, making good money, but suffering through challenging work and living conditions. For every one woman, there are roughly 50 men, and with most people living away from family and friends for long periods, social disorder and drug use are common. Despite these obstacles, Beaton enjoys a few friendships with other women and some men who also come from the east – those who can be trusted. And amongst the scary reality of working in these treacherous conditions, there are moments of beauty that are beautifully illustrated in this graphic format. Beaton’s story has a happy ending, as the comics she begins writing out west turn into a hugely successful career for her, so she was able to move back home to Cape Breton and make a decent living off her art. Still, the memories and experiences of the oil sands still haunt her, as this book depicts.

My Thoughts

Even though I was aware of how strange life is for those who work at the oil sands camps up north, reading about a female perspective like this reminds me of how difficult it would be to truly understand unless you lived it yourself. The constant sexual harassment alone is bad, but the fact that for a period of time she lived in the dorms along with these men, forced to expose herself to this constant treatment seems unbearable, which is reflected in her story as she nears the end of her time there. At one point, she laments that she is no longer treated as human, and this weariness she feels comes through clearly in the expressions she wears on her face. Afraid for her security, she locks her bedroom door every night, but men still try to get in, her doorknob jiggling becoming just one more noise she has to block out with her earplugs. After each difficult encounter, Beaton draws a single frame in which we can see her face and the emotions going on underneath, which replaces the inner dialogue we may see in a written narrative, but still manages to convey a wealth of information. It’s only when Beaton is alone with a trusted friend that her emotions burst out of her, although her frustrations are easily evident as the comic progresses.

The male behaviour is what’s making Beaton’s (and the other womens’) lives so difficult, but Beaton is quick to point out that the isolated living conditions are really to blame here. Her love of her hometown is evident, and there exists a special connection between those who come from out east – they can identify each other quickly because of their accents, and it’s a tight-knit community, so when Beaton arrives in Alberta she is invited to people’s homes for meals that her parents have arranged. At times she befriends certain men that she believes are ‘one of the good ones’, yet quickly disappointed when she discovers they are regularly cheating on their wives, which is apparently, endemic to these places. She questions whether her own father or close male friends would revert to these base behaviours if they were isolated like this for weeks at a time. She also grows frustrated at the number of men who approach her, claiming they ‘like her’ in a special way. She points out to them that they only think that because of where they are, and how few women there are, and simply being in the same place at the same time is no reason to start a relationship. The men joke that they are all taking bets on who will sleep with her first, which is just one of the comments she has to constantly put up with.

Alongside the horror of drug use, prostitution, sexual harassment and bizarre workplace politics, Beaton is also careful to highlight the positive aspects of this land. This comes through the fierce defense of the Indigenous people who are trying to prevent its destruction, the three-legged fox that sniffs around the worksites at night, and the incredible northern lights that arrive unannounced in their breathtaking beauty. It’s a book full of juxtaposition, but one that I refuse to give away like I do most of my other books; this one will remain in a place of pride on my shelf, but I’ll lend it out to those looking for a new perspective on a place we often hear about, but will never experience.

Sounds like a pretty harrowing time. Whenever we didn’t have a boyfriend in our youth, we all used to joke about going to Alaska because we were told there were twenty men to every woman – sounded wonderful at the time, but I guess that was because of our naivety. In reality I can see how scary it could be.

Totally, at first it sounds so fun, but when she lands there and begins to work, it sounds like a total nightmare.

I’ve heard only amazing things about this but I’ve avoided it because it does sound pretty harrowing. It is nice to know that she was able to move on and be successful in what she actually wanted to do.

It’s nicely balanced with humour and beauty too, so I wouldn’t worry about it being too bleak

That’s good to know. I know a lot of her work is funny but I hadn’t gotten that there was much humour to Ducks.

I mean, it’s not LOL on every page, but there is definitely some humour

I loved this book. I thought it was so well done.

I came away feeling like these living and working conditions can’t be good for anyone. I really hope they’ve improved over the last 20 years.

My brother is working in Alberta again right now… He’s working out of Grande Prairie I think.

I can’t say I know too much about the working conditions and how they’ve changed. I would hope they have improved (so many have since Covid) but I don’t know if that’s extended into those isolated workplaces.

I only just got around to reading this one last year, too, Anne: you’re not alone! Heheh

It’s one that I had on a list to write about on BIP and I might yet do so; there are so many layers and complications that I really found myself wanting to discuss it at the end.

That coyote scene! (For others who might be reading that as being the worst that can happen, it’s not, but it was still a sad scene, when she realises how hard it will be for this creature to survive in this human-altered landscape.)

yes the coyote scene! Those pinpricks of animal interaction and observation are wonderful little pauses in the narrative

It sounds so powerful. I don’t often read nonfiction graphic books but this one sounds well worth it. A lovely review.

Thank you! It’s a nice book, and because of its popularity up here, you should be able to hopefully find it down there soon

I’m not sure what oil sands are. Maybe that’s the Canadian name for something we have in the US, too. I can’t even fathom the audacity to try to just walk into someone’s room in the middle of the night. Like, there’s a blank space in my brain where that would exist.

I know it’s crazy.

The Oil Sands is a place in Northern Alberta where a type of oil is taken from the ground. It’s not drilled and pumped out like it typically is elsewhere, it’s a different viscosity or something so a few more things need to be done to prepare it.

https://www.capp.ca/oil/what-are-the-oil-sands/

This is a very industry-specific website that explains it, but to be clear, it’s very biased because its written by the producers themselves. The Oil Sands are quite desctructive to the environment too, which is what leonardo di Caprio and Jane Fonda flew up here to see a few years ago

How the hell did I forget Leo is an environmentalist??

He’s got….lots of different interests (smirk)