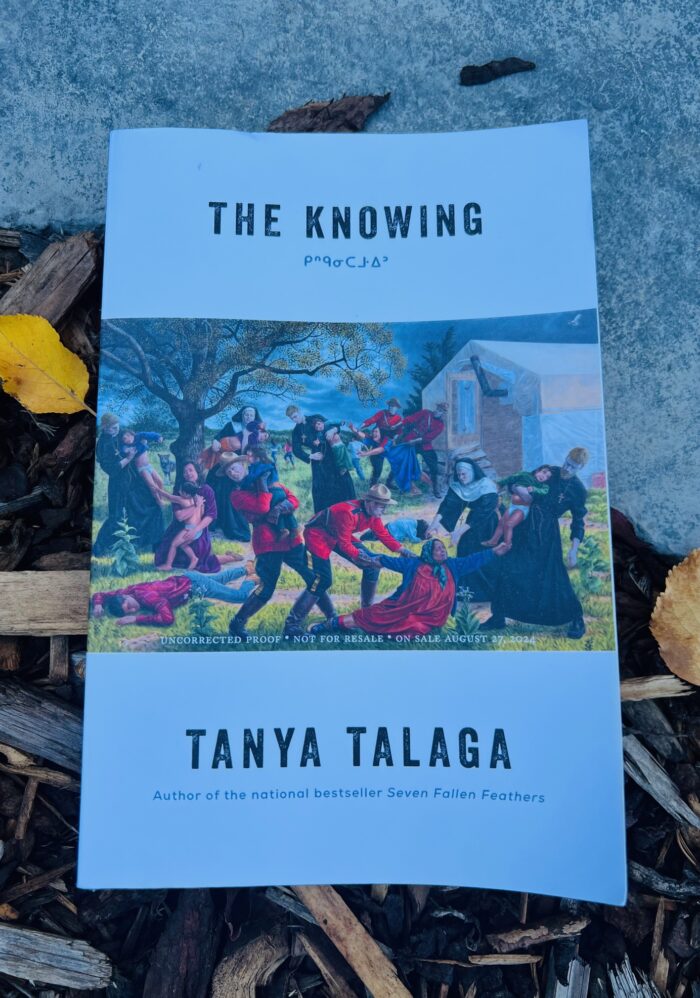

Book Review: The Knowing by Tanya Talaga

Many Canadian book-lovers will be aware of this latest release: The Knowing by Tanya Talaga hit store shelves at the end of August, is currently on the bestseller list, and will likely remain there for the next few months. A documentary by the same name (trailer below) was released at the same time as the book. September 30 is Truth and Reconciliation Day here in Canada, which I’ve written about in the past, but to honour that day this year I wanted to post my review of Talaga’s latest work of non-fiction which is dedicated to unspooling the horrific threads of the residential school system in Canada.

Book Summary

Talaga is an Indigenous journalist with a few books under her belt (see my review of one of them here), and is also widely known for her well-researched columns in our country’s major newspapers. Her latest book is an extensive history of residential schools, and how they came about in Canada, starting with the development of relations between European settlers and the Indigenous folks they invaded. She also details the signing of the treaties across Canada, and the subsequent Indian Act, which continues to this day, albeit having a few adjustments made to it since then. Shockingly, it was only in 1985 that the Indian Act was updated to ensure Indigenous women were given the same rights as Indigenous men; like so many other gestures, the attempts to right the wrongs done to the Indigenous population in Canada are all fairly recent. In addition to the valuable history lessons, Talaga dives into a mystery within her own family: the journey and final whereabouts of her great-great grandmother Annie, a woman born in North Ontario, but buried in an unmarked grave by the side of a major highway thousands of kilometers away.

My Thoughts

Research is something Talaga excels at, and the pages and pages of references she cites at the end of this book attest to the work she has put into this project. Unfortunately, many documents that detail the lives of Indigenous people are withheld from them, still locked away in the churches that governed their lives once the residential school system was established. I will remind people that the last residential school closed in 1996, and the first opened in the 1800s, so it is multiple generations of Indigenous folks that have lost access to their loved ones’ information, and are still in search of it today. Talaga’s story is one of hundreds of thousands like hers, many kids disappearing from the residential school systems, many of them without even a death certificate. She includes pictures of some of these documents and correspondence that she was able to find, but much of what was kept in residential schools has been purposely destroyed to cover up wrong-doing. Heartbreakingly, she finds a few letters from school administrators informing parents of their children’s death. In many cases, families weren’t allowed at their children’s burial, only informed of it weeks later. But as the grisly discovery in Kamloops suggests, many parents didn’t even get a letter, their children just never came home.

Because of the overwhelming number of statistics, research and history presented here, readers who are new to learning about the residential school system would likely find this book too detailed, not to mention the awful stories of medical experiments and torture enacted on children in these horrible places. However, for those of us who have read both fiction and non-fiction regarding the disgusting legacy of the residential school system, this is a sobering but valuable resource to continue your learning. Talaga furthers the work on this topic by providing helpful context in which to situate the history. She begins as far back as existing research will allow, but she also includes her experience of joining the Indigenous delegation trip to Rome in 2022 and then the subsequent papal apology tour. Later on in the book she visits a recently closed residential school with a survivor and previous pupil who comes face to face with the caretaker of the property who worked there while Talaga’s friend was still a student. This caretaker is friendly, happy to see a familiar face, but expresses dismay at the questions regarding the abuse he ignored. Even in the present day there are still deniers, those unwilling to face the horror they did not stop or question.

It goes without saying this is a challenging read. At just over 450 pages it’s a long book that covers a very dark time, but sometimes we need to force ourselves to bear witness to the difficult past. Reading about it and educating ourselves is the best way to start.

Great review – I’ve seen this of course but haven’t talked to many who have actually read it yet. Good to know what it will be like because I do want to read it. I know it will be a hard read when I get there though.

It is a hard read, but you are quite familiar with the Indigenous history here Karissa so I’m sure you won’t be as shocked as some of these revelations as others would. Definitely worth it!

It certainly does sound challenging but, as you say, important. It never ceases to surprise me how recently it is that some of these awful practices were ended.

This is the most shocking thing FF, how recent this is.

It is so important that people know about this kind of stuff! The movement to sweep historical racist atrocities under the rug in America is appalling.

It is appalling Laila, and unfortunately it’s happening everywhere! Perhaps not to the same extent up here in Canada, but simply telling these stories, making sure they aren’t lost is so important. And reading them means we are doing our part :)

This book sounds so detailed and long that I’m surprised it’s not published by a textbook company, like Cengage. Then again, what class would such a book fit in? Could even a college course devote so much time to this specific aspect from history? The fact that I know we would not encounter such a course speaks volumes.

It is detailed, but Talaga does a good job of weaving in her own personal history. It’s a book only a journalist could write, quite honestly. I will say that in the good news category, Canadian universities do have courses on this now, in fact, there’s a free course online that Canadians (maybe anyone) can take through the University of Alberta all about truth and reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples, and our history of colonialization.

https://www.ualberta.ca/en/admissions-programs/online-courses/indigenous-canada/index.html

This is on my TBR and I’m glad to know, in advance, that it’s over 400 pages. For some reason (maybe the cover design?) I thought it was more like the Anansi series (the Massey Lectures). Somewhere (maybe The Walrus?) I read an essay about her experience going to Rome and found that fascinating, so I’m pleased to hear that is a big part of this work. And I remember being overwhelmed by the references in Seven Fallen Feathers but also so impressed by how her expertise didn’t burden the prose at all; she keeps you engaged the whole time and lets the story speak for itself and those who want details or verifications can follow-up via the endnotes.

Yup it’s long and detailed, which I found in Seven Fallen Feathers as well, but her personal story keeps the pages moving for sure. The Rome experience is VERY interesting.